The Trail of Tears represents one of the darkest chapters in American history, when tens of thousands of Native Americans were forcibly removed from their ancestral homelands in the southeastern United States and marched to designated territories in present-day Oklahoma, resulting in thousands of deaths and immeasurable cultural devastation.

The Trail of Tears stands as one of the most shameful episodes in American history. Between 1831 and 1850, approximately 100,000 Native Americans were forcibly removed from their ancestral homelands in the southeastern United States and compelled to march hundreds of miles to designated "Indian Territory" west of the Mississippi River (present-day Oklahoma). This forced migration resulted in widespread suffering, death, and cultural devastation for the Indigenous peoples affected.

What began as a policy decision in Washington ended as a humanitarian catastrophe, with thousands perishing from exposure, disease, and starvation during the grueling journey. The Trail of Tears represents not just a historical event, but an ongoing legacy of trauma that continues to impact Native communities today.

Historical Context

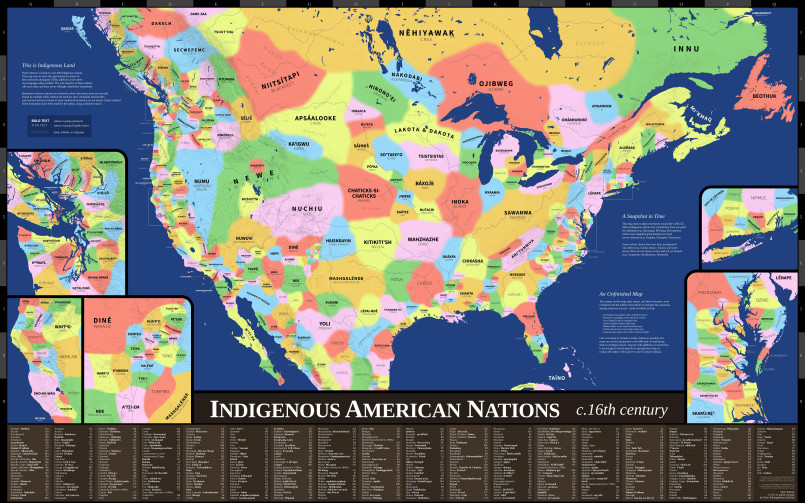

In the early 19th century, white settlers' demand for land grew exponentially, particularly after the discovery of gold on Cherokee land in Georgia in 1829. Despite earlier treaties guaranteeing Native Americans their territories, political pressure mounted to remove these tribes from their resource-rich lands.

President Andrew Jackson, who had gained fame as an "Indian fighter" before his presidency, became a driving force behind removal policies. His administration viewed Native Americans as impediments to progress and believed their removal would solve conflicts between tribal governments and states while opening valuable land for white settlement.

Many Native American nations had already adopted aspects of European-American culture, developed written languages, established formal governments, and even owned plantations and enslaved people. The Cherokee Nation specifically had developed a sophisticated governmental system with a written constitution. These adaptations, however, did not protect them from the federal government's determination to acquire their territories.

The Indian Removal Act of 1830

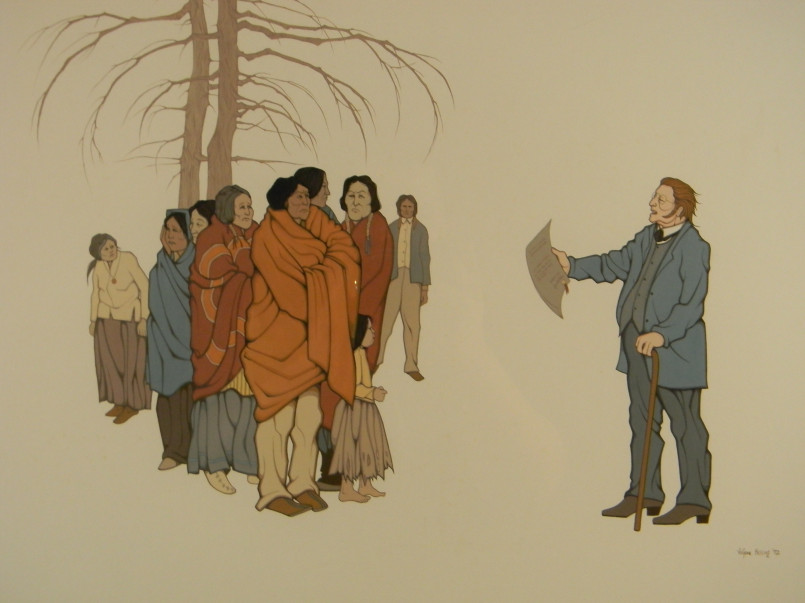

On May 28, 1830, President Andrew Jackson signed the Indian Removal Act into law, authorizing the president to negotiate with southern Native American tribes for their removal to federal territory west of the Mississippi River in exchange for their ancestral homelands.

While the law technically required voluntary consent through treaties, in practice, tremendous pressure and coercion were applied. When some tribal leaders signed removal treaties, they often did so without proper authority or against the wishes of the majority of their people. The Cherokee Nation challenged their removal through the U.S. legal system, resulting in the landmark Supreme Court case Worcester v. Georgia (1832).

In this case, Chief Justice John Marshall ruled that the Cherokee Nation was sovereign, making the removal treaties illegal. President Jackson, however, ignored the Supreme Court's decision, reportedly declaring, "John Marshall has made his decision; now let him enforce it." This blatant disregard for the Court's authority effectively greenlit the forced removals.

Affected Tribes

Five major tribes, often referred to as the "Five Civilized Tribes" by white settlers due to their adoption of certain European-American practices, were primarily affected by the Indian Removal Act:

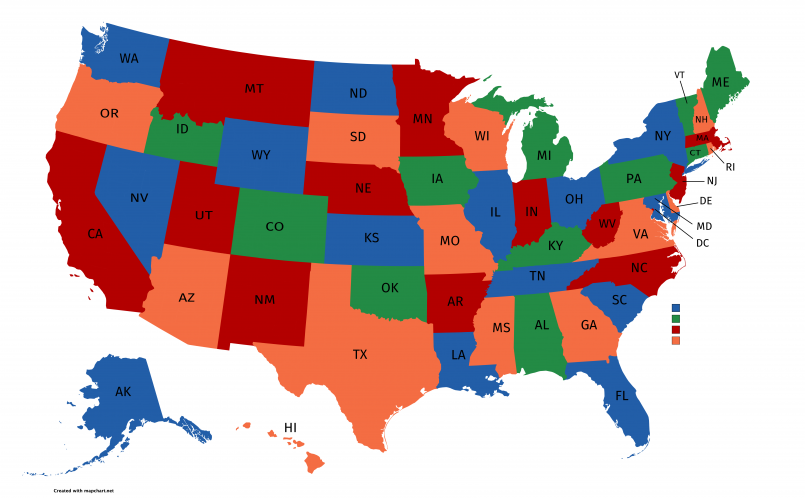

- Cherokee: Approximately 16,000 Cherokee were forcibly removed from Georgia, Alabama, Tennessee, and North Carolina in 1838-1839

- Muscogee (Creek): About 20,000 were removed from Alabama, Georgia, and Florida between 1834-1837

- Seminole: Around 4,000 were removed from Florida between 1832-1842, though many resisted through warfare

- Chickasaw: Approximately 4,000 were removed from Mississippi and Alabama between 1837-1850

- Choctaw: About 12,500 were removed from Mississippi, Alabama, and Louisiana between 1831-1833

Each tribe experienced its own removal timeline and unique hardships, but all suffered tremendously. The Choctaw removal, which began in 1831, was the first major removal and became a blueprint for later removals. When a Choctaw chief described the journey as a "trail of tears and death," the name became synonymous with the entire forced migration tragedy.

Journey Conditions

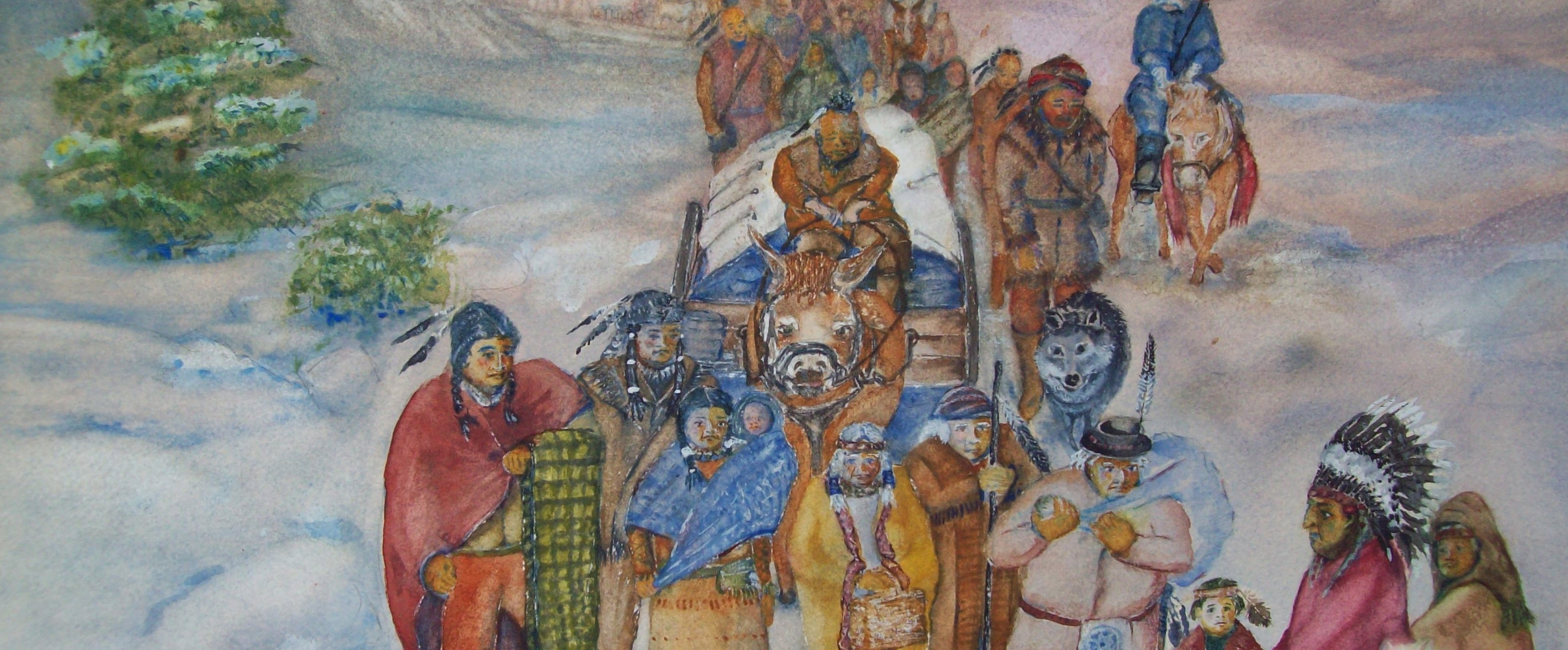

The conditions during the forced marches were catastrophically harsh. Most removals occurred during fall and winter, when food was scarce and weather conditions severe. The Cherokee removal in particular, which took place during the winter of 1838-1839, subjected people to freezing temperatures with inadequate clothing, shelter, and food.

Government preparations for the journey were woefully inadequate. Food rations were often spoiled or insufficient. Medical care was minimal despite rampant diseases including cholera, dysentery, whooping cough, and exposure-related illnesses. Families were often separated, and personal belongings had to be abandoned.

The journey covered approximately 800-1,200 miles depending on the route and starting point. Most people traveled on foot, though some went by boat along river routes. Those traveling by water faced different but equally dangerous conditions, with overcrowded boats and disease spreading rapidly in confined spaces.

Military escorts supervised the removals, sometimes providing protection but often treating the Native Americans as prisoners. Accounts from soldiers, missionaries, and survivors describe heart-wrenching scenes of suffering, with the dead sometimes left unburied along the trail as the groups were forced to continue their march without pause for proper mourning rituals.

Death Toll and Human Cost

The precise number of deaths during the Trail of Tears remains unknown, but historians estimate that approximately 4,000 Cherokee died during their removal alone-nearly a quarter of their total population. Across all tribes, the death toll may have exceeded 10,000 people.

Deaths occurred not only during the journey itself but also in the internment camps where Native Americans were held before departure and in the years immediately following relocation as communities struggled to establish themselves in unfamiliar territories with different agricultural conditions.

The human cost extended beyond the death toll. Families were torn apart, cultural practices disrupted, and entire ways of life fundamentally altered. The psychological trauma of forced removal created lasting wounds that would be passed down through generations.

Upon arrival in Indian Territory, the tribes faced new challenges: adapting to different environments, rebuilding social structures, and managing conflicts with plains tribes already inhabiting the region. The U.S. government often failed to provide promised supplies and protection, compounding the difficulties of establishing new communities.

Cultural Impact and Legacy

The Trail of Tears resulted in profound cultural disruption for all affected tribes. Sacred sites, traditional hunting grounds, and ancestral burial places were lost. The physical displacement severed connections to lands that held deep spiritual significance and were central to tribal identities.

Despite these devastating losses, tribal communities displayed remarkable resilience. In their new territories, they rebuilt governments, schools, and cultural institutions. The Cherokee established a new capital at Tahlequah (in present-day Oklahoma), where they reconstituted their government and educational system.

The trauma of removal became incorporated into tribal identities and oral histories, ensuring that future generations would remember what had occurred. This cultural memory has served as a foundation for modern Native American activism and efforts to preserve indigenous languages, traditions, and sovereignty rights.

The forced removals also established a troubling precedent for future U.S. government policies toward Native Americans, including further land cessions, the reservation system, and assimilation programs that continued well into the 20th century.

Memorials and Remembrance

Today, the Trail of Tears is commemorated through the Trail of Tears National Historic Trail, established by Congress in 1987. Administered by the National Park Service, this trail preserves sites, segments of the original routes, and commemorative markers across nine states.

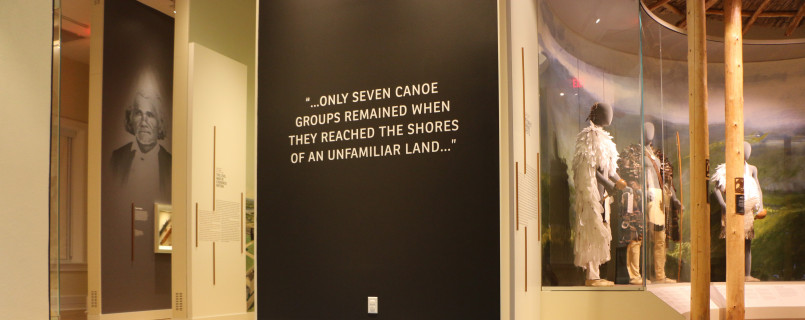

Annual commemorative walks, educational programs, and ceremonies help keep the memory of this tragic history alive. The Cherokee Nation holds an annual remembrance event, and numerous museums-including the Cherokee Heritage Center in Tahlequah, Oklahoma-maintain exhibits about the removal period.

In recent decades, there has been increasing recognition of the Trail of Tears as a significant human rights violation in American history. More comprehensive coverage in educational curricula and public history initiatives has helped bring this often-overlooked chapter of history into greater focus.

While acknowledgment of historical wrongs cannot undo the trauma inflicted, recognition of the Trail of Tears as a pivotal injustice has become an important part of broader discussions about historical accountability, indigenous rights, and the complex legacy of American expansion.

Frequently Asked Questions About Trail of Tears: 5 Tragic Facts About Native American Forced Relocation

What was the Trail of Tears?

The Trail of Tears was the forced relocation of Native American nations from their ancestral homelands in the southeastern United States to territories west of the Mississippi River in the 1830s and 1840s. The journey, often made on foot for hundreds of miles in harsh conditions, resulted in thousands of deaths from exposure, disease, and starvation.

Which Native American tribes were affected by the Trail of Tears?

The five major tribes affected were the Cherokee, Muscogee (Creek), Choctaw, Chickasaw, and Seminole, often referred to as the "Five Civilized Tribes" by white settlers. Other smaller tribes and bands were also removed during this period, including the Ponca, Ho-Chunk, Potawatomi, and several others.

Why did the U.S. government remove Native Americans from their lands?

The primary motivations were white settlers' demands for land, especially after gold was discovered on Cherokee territory in 1829, and President Andrew Jackson's belief that Native Americans and white settlers could not coexist. State governments, particularly Georgia, also wanted to eliminate independent tribal governments within their claimed borders and gain access to valuable resources.

How many people died during the Trail of Tears?

While exact numbers are difficult to determine, historians estimate that approximately 4,000 Cherokee died during their removal alone-about one-quarter of their population. Across all tribes, the death toll likely exceeded 10,000 people from exposure, disease, starvation, and the hardships of the journey.

Did any Native Americans resist removal?

Yes, resistance took many forms. The Cherokee Nation fought legally through the U.S. court system, resulting in the Supreme Court case Worcester v. Georgia, which ruled in their favor (though Jackson ignored the ruling). The Seminole actively resisted through warfare in what became known as the Second Seminole War (1835-1842). Small groups from various tribes hid in remote areas to avoid removal.

How long did the journey of the Trail of Tears take?

The journey typically took 4-6 months to complete, covering distances of 800-1,200 miles depending on the starting point and route. The Cherokee removal in 1838-1839 took place during winter, making conditions particularly deadly as they faced freezing temperatures, snow, and ice during their march.

How is the Trail of Tears remembered today?

Today, the Trail of Tears is commemorated through the Trail of Tears National Historic Trail, which preserves sites and segments of the original routes across nine states. Annual remembrance events, museum exhibits, and educational programs help keep this history alive. Many Native American communities continue to pass down oral histories of their ancestors' experiences during removal.