America's longest rivers have carved landscapes, powered cities, and shaped the nation's destiny for millennia. From the Mississippi's sprawling basin to the Yukon's wild frontier waters, these mighty waterways continue to serve as vital economic corridors, ecological treasures, and living monuments to the country's natural heritage.

America's vast landscape is defined by its mighty rivers-natural highways that have transported people, goods, and ideas since time immemorial. These flowing giants shaped the nation's development, determining where cities would rise, how commerce would flow, and how the country's natural resources would be harnessed. Today, they remain vital arteries for agriculture, industry, recreation, and ecological health.

From the expansive Mississippi-Missouri system that bisects the continent to the wild Yukon that cuts through Alaska's remote wilderness, these waterways tell the story of America itself-a tale of exploration, settlement, industry, and our ongoing relationship with the natural world. Let's explore the eleven longest rivers in the United States and discover what makes each one unique.

Mississippi-Missouri River System

The Mississippi-Missouri River system stands as the mightiest river network in North America and the fourth longest in the world. Together, they stretch an impressive 3,902 miles (6,275 km). The Missouri River, technically the main stem, begins in the Rocky Mountains of western Montana before joining the Mississippi at St. Louis.

The Mississippi River portion flows 2,320 miles (3,734 km) from its source at Lake Itasca, Minnesota to the Gulf of Mexico. This river system drains 41% of the continental United States, creating America's agricultural heartland and supporting more than 70 million people.

Since the early 19th century, the Mississippi has been essential for commerce, with Mark Twain famously calling it "the body of the nation." Today, the river carries over 500 million tons of cargo annually, including 60% of America's grain exports. The river system has been extensively engineered with levees, locks, and dams to control flooding and facilitate navigation.

Yukon River

Flowing 1,980 miles (3,190 km) from British Columbia through Alaska to the Bering Sea, the Yukon River is the third-longest river in North America and the longest in Alaska. This mighty waterway carved the remote landscapes of the far north long before human settlement, creating one of the largest salmon-producing river systems in the world.

During the Klondike Gold Rush of the 1890s, the Yukon became a vital transportation route for fortune-seekers. Today, it remains crucial for indigenous communities who have relied on its salmon runs for thousands of years. The river freezes solid during winter months, transforming into an ice highway for local travel.

Unlike most major American rivers, large portions of the Yukon remain wild and undeveloped, providing critical habitat for wildlife including moose, bears, and eagles. Its watershed spans 330,000 square miles-nearly the size of Texas and California combined.

Rio Grande

The Rio Grande stretches 1,896 miles (3,051 km) from the San Juan Mountains of southern Colorado to the Gulf of Mexico. For 1,254 miles, it forms the natural border between the United States and Mexico, making it one of the most politically significant waterways in North America.

Once called "El Río Bravo del Norte" (The Wild River of the North), the Rio Grande has supported human civilization for millennia. Ancient pueblos, Spanish colonies, and modern cities have all depended on its waters in an otherwise arid landscape.

Today, the river faces significant challenges. Intensive agricultural and urban water use has reduced its flow dramatically-in some stretches, it's been nicknamed the "Rio Sand." Nevertheless, the river basin remains culturally vibrant, home to unique borderland communities with rich bicultural heritage.

Arkansas River

The Arkansas River runs 1,469 miles (2,364 km) from the Rocky Mountains in Colorado to its confluence with the Mississippi River in Arkansas. As a major tributary of the Mississippi, it's played a crucial role in American westward expansion and continues to be an economic lifeline for the agricultural heartland.

Native American tribes including the Osage and Quapaw lived along its banks for centuries before European contact. Later, it served as a major transportation route for fur trappers, settlers, and steamboats. The river basin saw significant development during the 20th century with the McClellan-Kerr Arkansas River Navigation System, which created a 445-mile navigable waterway with 18 locks and dams.

Today, the Arkansas River supports diverse uses including irrigation for millions of acres of farmland, hydroelectric power generation, and recreation. The upper reaches in Colorado are famous for world-class whitewater rafting and kayaking, while the lower portions support commercial shipping.

Colorado River

Though not among the longest at 1,450 miles (2,330 km), the Colorado River may be the most managed and contested waterway in America. From its headwaters in Rocky Mountain National Park to the Gulf of California in Mexico, this powerful river carved the Grand Canyon and now sustains nearly 40 million people across seven U.S. states and two Mexican states.

The Colorado's impact on the American West cannot be overstated. Its waters made possible the transformation of desert landscapes into agricultural powerhouses and booming metropolitan areas. The river has been tamed by massive engineering projects, including Hoover Dam and Glen Canyon Dam, which created Lake Mead and Lake Powell respectively.

However, overallocation, drought, and climate change have placed the Colorado River in crisis. Since the 1960s, it rarely reaches its natural delta in Mexico, and major reservoirs have dropped to historic lows. The river exemplifies both the triumphs of human ingenuity and the consequences of unsustainable water management.

Ohio River

The Ohio River flows 981 miles (1,579 km) from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania to Cairo, Illinois, where it joins the Mississippi. Formed by the confluence of the Allegheny and Monongahela rivers, the Ohio drains parts of 14 states and serves as both a vital transportation corridor and a boundary between the Midwest and South.

Historically, the Ohio River played a crucial role in America's westward expansion after the Revolutionary War. Later, it gained significance as the symbolic dividing line between slave and free states, with many enslaved people crossing it to freedom via the Underground Railroad.

Today, the Ohio remains one of America's busiest commercial waterways, carrying over 184 million tons of cargo annually. Its basin is home to diverse industries including steel production, energy, and manufacturing. The river has also experienced significant environmental recovery after decades of pollution, though challenges remain.

Columbia River

The Columbia River flows 1,243 miles (2,000 km) from British Columbia through Washington and Oregon to the Pacific Ocean. As the largest river in the Pacific Northwest and the fourth-largest by volume in North America, it drains a watershed roughly the size of France.

For thousands of years, the Columbia served as the lifeblood of indigenous cultures, particularly due to its legendary salmon runs. The river gained prominence in American history when Lewis and Clark followed it to the Pacific in 1805. Later, it became central to regional development through the New Deal-era construction of 14 major hydroelectric dams.

These massive dams transformed the Columbia from a free-flowing river to a series of reservoirs, producing nearly half of all U.S. hydroelectric power and enabling irrigation of over 600,000 acres of farmland. However, this engineering marvel came at an ecological cost, particularly to salmon populations that declined by over 90%. Today, significant efforts focus on balancing power generation, agriculture, and ecological restoration.

Snake River

The Snake River, the Columbia's largest tributary, winds 1,078 miles (1,735 km) through Wyoming, Idaho, Oregon, and Washington. Named for the S-shaped hand sign made by Shoshone people to identify themselves, this powerful waterway carved North America's deepest river gorge-Hells Canyon-which plunges deeper than the Grand Canyon.

The Snake River Plain was shaped by massive volcanic eruptions and cataclysmic Ice Age floods that created one of the country's most unique landscapes. Early pioneers followed portions of the river along the Oregon Trail, with many fording its waters at dangerous crossings.

Today, the Snake supports extensive agriculture through irrigation, particularly Idaho's famous potato industry. Its dams generate significant hydroelectric power, though like the Columbia, these impoundments have significantly impacted salmon and steelhead populations, leading to ongoing debates about potential dam removals to restore fish migration routes.

Red River

The Red River (also called the Red River of the South) flows approximately 1,360 miles (2,190 km) from its headwaters in Texas through Oklahoma, Arkansas, and Louisiana before joining the Mississippi River. Its name derives from the reddish color of its waters, caused by red clay sediment.

This river has long formed a natural boundary, historically separating United States territory from Spanish and later Mexican lands. The area around the Red River was central to the complex history of the Caddo Confederacy and other indigenous nations before European settlement.

The Red River's most distinctive feature is the Great Raft-a natural logjam that once stretched over 160 miles-which prevented navigation until its removal in the late 19th century. Today, the river supports agriculture, recreation, and serves as an important ecological corridor despite challenges from saltwater intrusion and ongoing flood control efforts.

Saint Lawrence River

The Saint Lawrence River flows 744 miles (1,197 km) from Lake Ontario to the Atlantic Ocean, forming part of the border between the United States and Canada. While not entirely within U.S. borders, this massive waterway is crucial to North American commerce as the outlet of the Great Lakes, which contain 21% of the world's surface freshwater.

Indigenous peoples have lived along the Saint Lawrence for millennia, with the Iroquois calling it "Kaniatarowanenneh" (big waterway). French explorer Jacques Cartier first navigated it in 1535, establishing it as the primary route for European exploration and settlement of North America's interior.

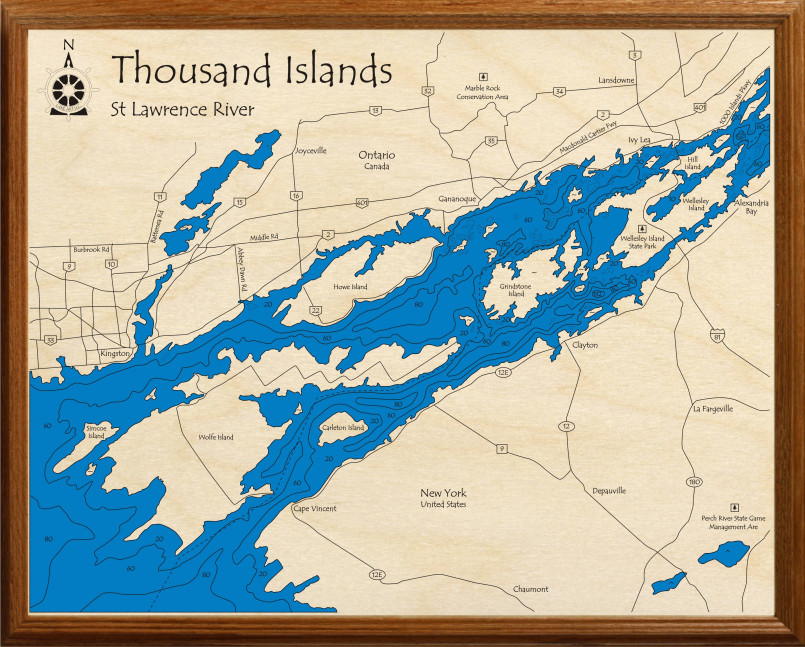

The completion of the Saint Lawrence Seaway in 1959-a massive engineering project with locks, canals, and channels-transformed the river into a navigable route for ocean-going vessels, connecting Great Lakes cities to global markets. The river's Thousand Islands region, with its 1,864 islands, remains a popular tourist destination and ecological treasure.

Tennessee River

The Tennessee River flows 652 miles (1,049 km) from Knoxville through Alabama, briefly into Mississippi, and back into Tennessee before joining the Ohio River at Paducah, Kentucky. As the largest tributary of the Ohio River, it drains portions of seven states across the southeastern United States.

The Tennessee River valley has been inhabited for at least 10,000 years, with the river supporting advanced Mississippian culture settlements before European contact. During the Civil War, the river's strategic importance led to several major battles along its course.

The river was fundamentally transformed in the 1930s and 1940s by the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA), one of America's most ambitious public works projects. The TVA constructed a system of 9 dams on the main river (and 42 more on tributaries), converting the Tennessee into a series of reservoirs. This massive project controlled flooding, provided electricity to a previously underserved region, and created new opportunities for recreation and commerce.

Frequently Asked Questions About 11 Longest Rivers in USA: Ancient Waterways That Shaped America

Which is the longest river in the United States?

The Mississippi-Missouri River system is the longest river system in the United States, measuring 3,902 miles (6,275 km) in total length. The Missouri River portion is technically the longer main stem, while the Mississippi portion is the larger by water volume.

How have these rivers influenced American history?

America's major rivers have profoundly shaped national development by determining settlement patterns, providing transportation corridors for exploration and commerce, enabling agricultural development through irrigation, generating hydroelectric power, and establishing natural boundaries. Rivers like the Mississippi facilitated westward expansion, while the Ohio River served as a dividing line between free and slave states before the Civil War.

Which river generates the most hydroelectric power?

The Columbia River generates the most hydroelectric power in the United States, producing approximately 44% of the country's total hydroelectric generation. Its 14 major dams, including Grand Coulee Dam (the largest power station in the US), have transformed the river into a major energy producer for the Pacific Northwest.

What are the main environmental challenges facing America's rivers today?

Major environmental challenges include water scarcity and overallocation (especially in the Colorado River basin), agricultural runoff causing nutrient pollution, habitat fragmentation from dams, declining fish populations, invasive species, industrial contamination, and climate change impacts including altered flow patterns and increased flooding or drought severity.

Can you visit these rivers for recreation?

Yes, all of America's major rivers offer recreational opportunities. The Colorado and Arkansas rivers are famous for whitewater rafting, while the Mississippi and Ohio support riverboat cruises. The Columbia, Snake, and Tennessee rivers have extensive reservoir systems ideal for boating and fishing. The Thousand Islands region of the Saint Lawrence is a popular tourist destination, and the Yukon offers wilderness canoeing and kayaking opportunities.

How have dams impacted these river systems?

Dams have fundamentally transformed America's rivers, controlling flooding, generating hydroelectricity, creating reservoirs for recreation, and enabling irrigation and navigation. However, they've also disrupted natural flow regimes, blocked fish migration, altered water temperatures, trapped sediment, and fragmented habitats. The environmental impacts have been particularly severe for migratory fish species like salmon in the Columbia and Snake river systems.