The Oregon Trail, stretching nearly 2,000 miles from Missouri to Oregon, became the pathway for America's dramatic westward expansion in the mid-1800s. Over 400,000 settlers braved dangerous river crossings, harsh weather, disease, and rugged terrain in search of new opportunities and land in the West, forever changing the nation's landscape and destiny.

The Oregon Trail stands as one of the most significant migration routes in American history, stretching nearly 2,000 miles from Independence, Missouri, to Oregon's Willamette Valley. Between 1840 and 1860, approximately 400,000 pioneers traveled this arduous path, propelling America's westward expansion and fulfilling what many believed was the nation's "manifest destiny" to spread across the continent.

These brave travelers packed their belongings into covered wagons drawn by oxen, leaving behind comfortable lives for the promise of fertile farmland, gold, religious freedom, and new opportunities in the western territories. Their journey would take 4-6 months of grueling travel across prairies, deserts, and mountains, forever changing the American landscape and the lives of those who called these lands home.

Origins of the Oregon Trail

The Oregon Trail's roots can be traced to early fur trappers and explorers who first mapped routes through the western wilderness in the early 1800s. Meriwether Lewis and William Clark's famous expedition (1804-1806) opened American eyes to the western territories, but it was fur trader Robert Stuart who first identified much of what would become the Oregon Trail while traveling eastward from Astoria in 1812-1813.

The trail gained significant attention in the 1840s when economic depression gripped the eastern United States, making the promise of free land in Oregon particularly appealing. In 1843, the "Great Migration" saw approximately 1,000 pioneers make the journey west, establishing the trail as a viable route for families seeking a fresh start.

The federal government actively encouraged westward expansion through the Oregon Donation Land Act of 1850, which granted 320 acres to any white settler and an additional 320 acres to his wife. This generous land policy, combined with promotional literature distributed in eastern states, fueled migration along the trail until the completion of the transcontinental railroad in 1869 made the wagon journey largely obsolete.

Life on the Trail

Preparing for the Oregon Trail journey required careful planning and significant resources. Families typically needed $500-$1,000 (equivalent to about $15,000-$30,000 today) to purchase a wagon, oxen teams, supplies, and food. Most travelers departed in spring, aiming to cross the treacherous Rocky Mountains before winter snowfall.

The covered wagon, often romantically called a "prairie schooner" because its canvas top resembled a ship's sail, served as both transportation and home. These wagons measured about 10 feet long by 4 feet wide, with most possessions stored inside while travelers typically walked alongside to reduce strain on the animals. Oxen were preferred over horses because they had greater endurance, strength, and were less likely to be stolen by Native Americans.

Daily life followed a predictable rhythm. Pioneers typically:

- Woke before dawn

- Traveled 15-20 miles per day

- Stopped midday to rest the animals

- Formed circular wagon corrals at night for protection

- Assigned watch duties to guard against threats

Women maintained domestic responsibilities while traveling, cooking meals over campfires, washing clothes in streams, caring for children, and often driving wagons. Men hunted for supplemental food, managed livestock, and handled wagon repairs. Despite these traditional divisions, the trail often blurred gender roles as survival demanded flexibility.

Dangers and Challenges

The 2,000-mile journey was fraught with hazards that claimed the lives of approximately one in ten travelers. Contrary to popular belief, attacks by Native Americans were relatively rare compared to other dangers. The most common causes of death included:

Disease claimed more lives than any other factor, with cholera being particularly devastating. This bacterial infection could kill within hours and spread rapidly through contaminated water supplies at crowded river crossings. Other common ailments included dysentery, typhoid fever, mountain fever, and smallpox.

River crossings presented serious hazards, with drowning accounting for many deaths. The Kansas, North Platte, and Snake Rivers were especially dangerous, forcing pioneers to caulk their wagons and float them across when ferries weren't available, or attempt to ford shallower sections that could still hide treacherous currents.

Accidents were commonplace - wagons overturned, firearms discharged accidentally, and travelers were sometimes crushed by wagon wheels or trampled by livestock. The grueling pace and physical demands led to exhaustion that increased the likelihood of fatal mistakes.

Weather extremes posed significant challenges, from scorching heat across the plains and deserts to freezing conditions in mountain passes. The Donner Party tragedy of 1846-1847 illustrates the danger of starting too late - trapped by early snows in the Sierra Nevada mountains, some members resorted to cannibalism to survive.

Famous Landmarks Along the Oregon Trail

The Oregon Trail was marked by distinctive natural features that served as navigational aids and milestones for weary travelers. Many became symbolic gathering points where pioneers left messages for those following behind.

Chimney Rock in present-day Nebraska rose nearly 300 feet above the surrounding landscape, visible for days before travelers reached it. This distinctive spire served as confirmation that pioneers were on the correct path and became one of the most mentioned landmarks in trail diaries.

Independence Rock, the massive granite dome in Wyoming, earned the nickname "The Register of the Desert" because thousands of pioneers carved their names into its surface. Travelers aimed to reach this landmark by July 4th (Independence Day), knowing that arriving later meant risking early snowfall in the mountains ahead.

Other significant landmarks included:

- Fort Laramie in Wyoming - a crucial resupply point and military outpost

- South Pass - a relatively gentle crossing of the Continental Divide

- Fort Bridger - founded by famous mountain man Jim Bridger

- The Blue Mountains - challenging terrain signaling the approaching end of the journey

Impact on Native Americans

The massive migration along the Oregon Trail had devastating consequences for Native American populations. The trail cut directly through territories belonging to numerous tribes including the Pawnee, Sioux, Shoshone, and Nez Perce, forever altering their way of life.

Initially, many tribes assisted travelers, serving as guides, trading supplies, and helping with river crossings. However, as migration increased, tensions grew. The wagons disrupted buffalo migration patterns and damaged hunting grounds. Travelers' livestock consumed grass needed for native horses, and pioneers cut trees for firewood, depleting important resources.

More significantly, the newcomers brought deadly diseases to which Native populations had little immunity. Smallpox, cholera, and measles ravaged tribes, sometimes wiping out entire villages before direct contact with settlers even occurred.

The U.S. government negotiated treaties that increasingly confined Native Americans to reservations, opening their ancestral lands to settlement. The trail itself became a symbol of this displacement, with each wagon that passed representing further encroachment on indigenous territories.

Cultural Legacy

The Oregon Trail has embedded itself deeply in American culture and national identity. It represents core American values of self-reliance, perseverance, and the pursuit of opportunity. The pioneers' willingness to risk everything for a better life has become central to how Americans understand their national character.

Literature and art have celebrated the trail experience since the migration itself, with pioneers' diaries providing firsthand accounts that still captivate readers today. Writers like Francis Parkman published influential accounts, while artists like Albert Bierstadt romanticized the western landscape in paintings that inspired further migration.

In popular culture, the trail gained renewed attention through the educational computer game "The Oregon Trail," first developed in 1971 and played by generations of American schoolchildren. The game's infamous line "You have died of dysentery" became a humorous cultural reference point while still educating players about historical challenges.

The trail experience influenced American fashion, cuisine, music, and folklore. Country-western music, rodeos, and the entire cowboy aesthetic draw partly from cultural elements that evolved during the westward expansion. The covered wagon became an enduring symbol of American pioneering spirit, appearing in countless films, advertisements, and public monuments.

The Oregon Trail Today

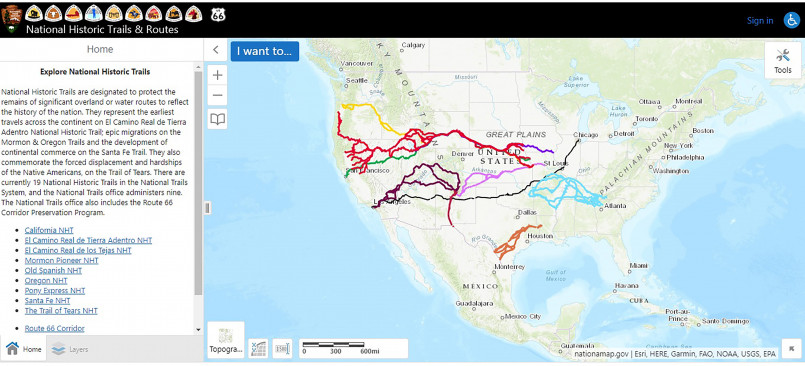

Today, approximately 300 miles of original wagon ruts remain visible across the American landscape, protected as part of the Oregon National Historic Trail administered by the National Park Service. Modern travelers can follow much of the original route by car along highways that parallel the historic path.

Numerous museums and interpretive centers dot the trail, including the National Historic Oregon Trail Interpretive Center in Baker City, Oregon, and the End of the Oregon Trail Interpretive Center in Oregon City. These facilities offer visitors the opportunity to see authentic wagons, tools, and personal items carried by pioneers.

Annual reenactments in communities along the trail keep historical memories alive, with participants dressing in period clothing and sometimes traveling short distances in authentic wagons. These events help modern Americans connect with the challenges faced by their ancestors.

While celebrating the courage and determination of the pioneers, many trail sites now also acknowledge the impact on Native American communities, offering more balanced interpretations that recognize multiple perspectives on westward expansion.

Frequently Asked Questions About The Oregon Trail: 10 Amazing Facts About America's Historic Westward Expansion

How long did it take to travel the Oregon Trail?

The journey typically took 4-6 months to complete, covering approximately 15-20 miles per day. Most pioneers started in spring (April-May) to ensure they would cross the mountains before winter snowfall. The timing was critical, as demonstrated by tragedies like the Donner Party, who started too late and became snowbound in the Sierra Nevada mountains.

What did people eat on the Oregon Trail?

Pioneers relied on staples including flour, bacon, coffee, sugar, and salt. They supplemented these supplies by hunting (bison, deer, and small game), fishing, and gathering berries and edible plants along the route. Many families brought milk cows for fresh dairy. Meals were simple-biscuits, salt pork, coffee, and occasional stews. Food preservation was challenging, and spoilage was common, especially during hot weather.

Why did people risk the dangerous journey west?

People were motivated by several factors: economic opportunity (free land under the Donation Land Act offered 640 acres to married couples), escape from economic depression in the East, gold discoveries in California, religious freedom (particularly for Mormons heading to Utah), health benefits (the West was promoted as having a climate that cured respiratory diseases), and adventure. Many genuinely believed in Manifest Destiny-that Americans were destined to expand across the continent.

Did children go to school while traveling the Oregon Trail?

Formal education was largely suspended during the journey, but many parents continued teaching their children using family Bibles and basic schoolbooks they brought along. Some wagon trains designated a person to teach children during evening rest periods. Many children kept diaries of their journey, improving their writing skills while documenting this historic migration. The trail itself was considered an education in practical skills, geography, and natural history.

What happened to the Oregon Trail after the transcontinental railroad was completed?

The completion of the transcontinental railroad in 1869 dramatically reduced Oregon Trail traffic, as travelers could reach the West Coast in a week rather than months. The trail continued to be used by settlers heading to areas not directly served by rail, but in significantly smaller numbers. By the 1880s, the trail had largely transformed into local roads connecting established communities, while many sections were abandoned and gradually reclaimed by nature.

How accurate is the Oregon Trail computer game compared to the historical reality?

While the classic game captures some authentic elements-like river crossings, hunting, and disease outbreaks-it necessarily simplifies the complex reality pioneers faced. The game accurately represents major landmarks and the general route, but cannot fully convey the physical exhaustion, emotional toll, and complex social dynamics of wagon trains. The game's focus on disease is historically accurate (disease was the biggest killer on the trail), though the famous line 'You have died of dysentery' has become more prominent in popular culture than in actual trail diaries.