The Electoral College is the system the United States uses to elect its president, not through direct popular vote but through a group of electors who cast votes based on their state's election results. This system has decided American presidents for over 200 years, sometimes producing winners who lost the popular vote.

Every four years, Americans go to the polls to elect a president. Yet many are surprised to learn they're not actually voting directly for their preferred candidate. Instead, they're participating in a complex system called the Electoral College that ultimately determines who becomes president of the United States.

The Electoral College has been the subject of controversy throughout American history, especially in elections where the winner of the popular vote did not become president. Understanding how this system works is essential for grasping American democracy and the unique way the United States selects its leader.

What Is the Electoral College?

The Electoral College is not a place but a process. It's a group of 538 people, known as electors, who meet in their respective states after the general election to cast their official votes for president and vice president.

These 538 electoral votes correspond to the total number of representatives in Congress-435 members in the House of Representatives, 100 senators, plus 3 electors for the District of Columbia (granted by the 23rd Amendment). A candidate needs a majority of these electoral votes-at least 270-to win the presidency.

How the Electoral College Works

The Electoral College process follows several distinct steps:

1. General Election: When citizens vote on Election Day (the Tuesday after the first Monday in November), they're actually voting for a slate of electors who have pledged to support a particular candidate.

2. Allocation of Electors: In 48 states and Washington, D.C., the candidate who wins the popular vote receives all of that state's electoral votes. This is known as the "winner-take-all" system. Only Maine and Nebraska use a different method, allocating two electoral votes to the statewide winner and the remainder to the winner of each congressional district.

3. Selection of Electors: The winning candidate's political party in each state selects the electors, typically choosing party loyalists, state officials, or people with close ties to the candidates.

4. Electoral Vote: The electors meet in their respective state capitals on the first Monday after the second Wednesday in December to cast their votes. These votes are then sent to Congress.

5. Congressional Certification: On January 6th following the election, Congress meets in joint session to count the electoral votes and officially certify the winner.

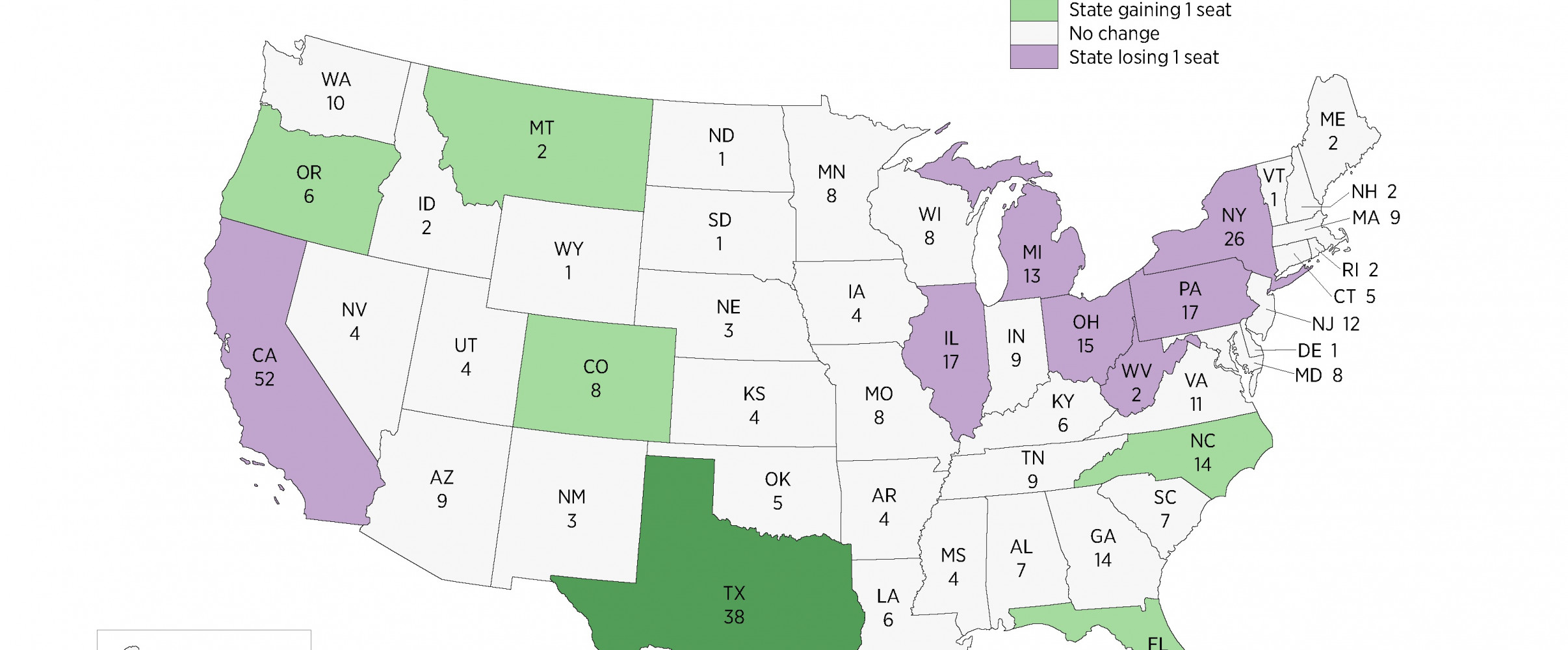

How Electoral Votes Are Distributed

Electoral votes are not distributed evenly by population, which creates some of the system's most controversial aspects:

- California has the most electoral votes (55), followed by Texas (38), Florida (29), and New York (29).

- The least populous states like Wyoming, Vermont, and Alaska have 3 electoral votes each.

- Because each state receives electoral votes equal to its total congressional representation (House members plus two senators), less populous states have proportionally more electoral power per voter than more populous states.

For example, Wyoming has one electoral vote per approximately 190,000 residents, while California has one electoral vote per approximately 720,000 residents. This means a vote in Wyoming carries nearly four times the electoral weight of a vote in California.

The History and Purpose of the Electoral College

The Electoral College was established in Article II, Section 1 of the Constitution and modified by the 12th Amendment in 1804. The Founding Fathers created this system for several key reasons:

1. Compromise: It represented a compromise between those who wanted the president elected by Congress and those who favored a popular vote.

2. Federalism: It preserved the federal character of the nation by ensuring states, as entities, play a crucial role in selecting the president.

3. Protection against uninformed voting: In an era without mass communication, the founders worried that citizens would lack sufficient information about candidates from other regions and would simply vote for "favorite sons" from their states.

4. Buffer against "mob rule": Some founders worried about the dangers of direct democracy and wanted educated electors to make the final decision.

5. Slave state influence: The system increased the influence of southern slave states through the Three-Fifths Compromise, which counted enslaved people as three-fifths of a person when determining a state's representation in the House (and thus its electoral votes).

Electoral College vs. Popular Vote

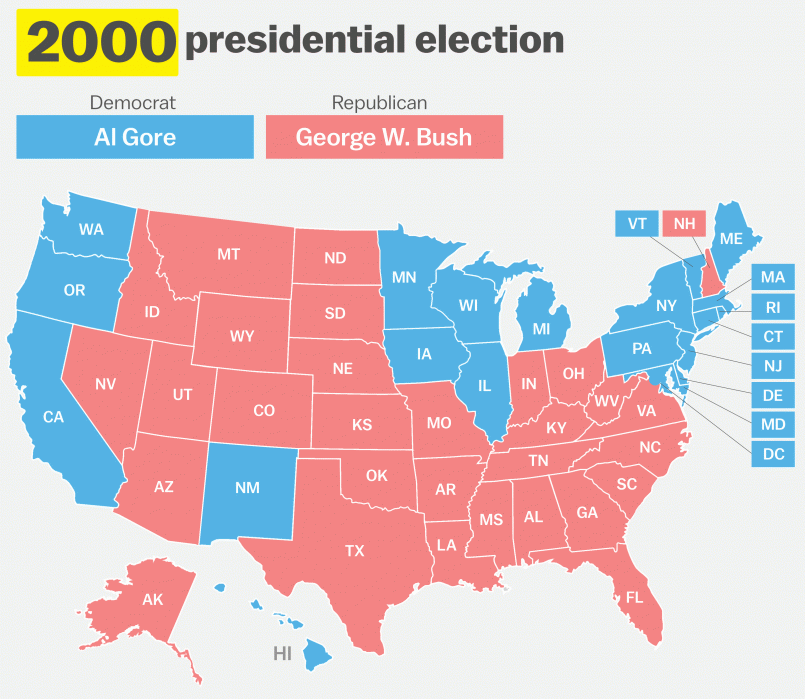

In most presidential elections, the Electoral College winner also wins the popular vote. However, five presidents have won the Electoral College while losing the popular vote:

- John Quincy Adams (1824): Lost to Andrew Jackson by 44,804 votes

- Rutherford B. Hayes (1876): Lost to Samuel Tilden by 264,292 votes

- Benjamin Harrison (1888): Lost to Grover Cleveland by 95,713 votes

- George W. Bush (2000): Lost to Al Gore by 543,895 votes

- Donald Trump (2016): Lost to Hillary Clinton by 2,868,686 votes

These discrepancies happen because the winner-take-all system in most states can amplify small victories in key states while discounting large margins in others. A candidate can win several large states by slim margins while losing others by substantial margins, resulting in an Electoral College victory despite losing the nationwide popular vote.

Faithless Electors: Can Electors Vote Differently?

Historically, electors were expected to use their judgment when voting. Today, they're generally expected to vote for the candidate who won their state's popular vote. However, "faithless electors" occasionally vote contrary to expectations.

Throughout American history, there have been over 150 faithless electors, though none has ever changed the outcome of an election. In response to this potential issue:

- 33 states plus the District of Columbia have laws that require electors to vote according to their pledge

- In 2020, the Supreme Court unanimously ruled in Chiafalo v. Washington that states can enforce laws that punish or remove faithless electors

Criticisms of the Electoral College

Critics of the Electoral College raise several significant concerns:

1. Undemocratic: It can result in presidents who lost the popular vote, seemingly contradicting the principle of majority rule.

2. Disproportionate influence: It gives smaller states disproportionate power per voter.

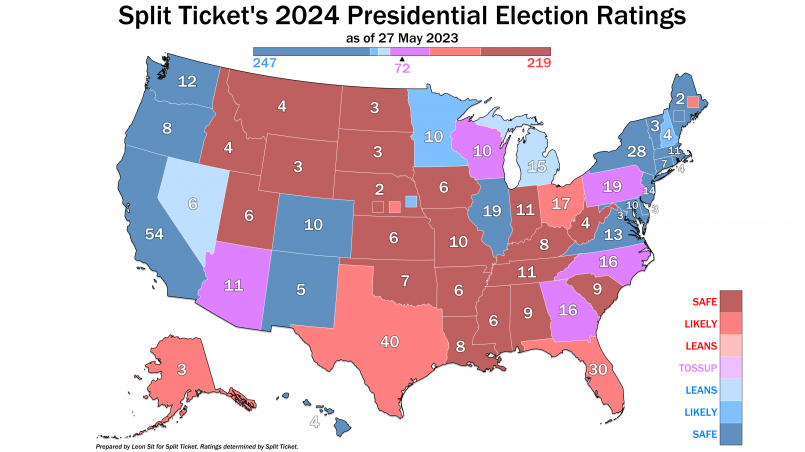

3. Battleground state focus: Candidates focus primarily on "swing states" or "battleground states" while largely ignoring reliably red or blue states, meaning most Americans live in states that receive little campaign attention.

4. Voter suppression: In solid red or blue states, voters for the minority party may feel their votes don't matter, potentially reducing turnout.

5. Third-party disadvantage: The winner-take-all system makes it nearly impossible for third-party candidates to win electoral votes.

Defenses of the Electoral College

Supporters of the Electoral College argue that it has several important benefits:

1. Federalism: It preserves the federal nature of the United States, treating presidential elections as a collection of state elections rather than a single national contest.

2. Rural representation: It prevents campaigns from focusing exclusively on densely populated urban centers and forces candidates to build broader geographic coalitions.

3. Moderation: It encourages candidates to appeal to the center rather than to extremes, as they must win diverse swing states.

4. Clarity: It typically produces clear winners and avoids nationwide recounts that would be necessary in close popular vote elections.

5. Stability: It has provided stable transitions of power for over two centuries, even during contentious elections.

Reform Proposals

Various alternatives to the current Electoral College system have been proposed:

1. Direct Popular Vote: Abolish the Electoral College entirely and elect the president by nationwide popular vote. This would require a constitutional amendment.

2. National Popular Vote Interstate Compact (NPVIC): This is an agreement among states to award all their electoral votes to the national popular vote winner, regardless of who wins in their state. It would take effect when enough states join to control 270 electoral votes. Currently, 15 states and D.C. have joined, representing 196 electoral votes.

3. Proportional Allocation: Award electoral votes proportionally to each candidate based on their share of the state's popular vote, similar to how many democratic countries allocate parliamentary seats.

4. Congressional District Method: Expand the system currently used by Maine and Nebraska nationwide, where two electoral votes go to the statewide winner and the rest to the winner of each congressional district.

The Future of the Electoral College

Despite periodic calls for reform, changing the Electoral College faces significant obstacles:

1. Constitutional hurdles: Abolishing the Electoral College would require a constitutional amendment, needing two-thirds approval in both houses of Congress and ratification by three-fourths (38) of the states.

2. Political resistance: Smaller states that benefit from the current system would likely oppose changes that dilute their influence.

3. Partisan considerations: Support for or opposition to Electoral College reform often aligns with which party believes it would benefit from a change.

The debate over the Electoral College reflects broader tensions in American democracy between majority rule and minority protection, federal principles and national unity, and tradition versus reform. As American demographics and political coalitions continue to evolve, discussions about the best way to elect the president will likely persist.

Understanding the Electoral College isn't just academic-it shapes campaign strategies, influences which voters candidates prioritize, and ultimately determines who leads the world's oldest constitutional democracy.

Frequently Asked Questions About Electoral College Explained: 10 Simple Facts About How US Presidents Are Actually Elected

Why was the Electoral College created?

The Electoral College was created as a compromise between those who wanted Congress to select the president and those who preferred direct popular election. It was designed to ensure smaller states had meaningful influence in presidential elections, to preserve the federal nature of the United States, and to provide a buffer between popular passions and the selection of the president.

Can a president win the Electoral College but lose the popular vote?

Yes, this has happened five times in U.S. history. The most recent instances were in 2000 when George W. Bush defeated Al Gore despite receiving fewer total votes, and in 2016 when Donald Trump defeated Hillary Clinton despite receiving nearly 3 million fewer votes nationwide. This occurs because of the winner-take-all system used in most states.

What happens if no candidate receives 270 electoral votes?

If no candidate receives a majority of electoral votes (at least 270), the election is decided by the House of Representatives in what's called a contingent election. Each state delegation gets one vote, regardless of its size. The Senate chooses the Vice President, with each senator getting one vote. This has happened twice: in 1800 and 1824.

Are electors required to vote for the candidate who won their state?

Traditionally, electors vote for the candidate who won their state, but historically some 'faithless electors' have voted differently. As of 2020, 33 states and D.C. have laws binding electors to vote according to their pledge. The Supreme Court ruled in 2020 that states can legally enforce these laws by removing or penalizing faithless electors.

How does the Electoral College affect campaign strategy?

The Electoral College dramatically shapes campaign strategy by focusing candidates' attention on 'swing states' or 'battleground states' where either party could win. States that reliably vote for one party receive far less attention. This is why states like Florida, Pennsylvania, Michigan, and Wisconsin often see intense campaigning while states like California or Texas see relatively little despite their large populations.

Could the Electoral College ever be abolished?

Abolishing the Electoral College would require a constitutional amendment, needing two-thirds approval in both houses of Congress and ratification by three-fourths (38) of states. This high threshold makes it difficult to abolish. An alternative approach is the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact, where states agree to award their electoral votes to the national popular vote winner, which would effectively bypass the current system without a constitutional amendment.