Before becoming the 28th state, Texas existed as an independent republic for nearly a decade. This fascinating chapter in American history saw the Lone Star State establish its own government, defend its borders, and negotiate with world powers as a sovereign nation.

Deep in the heart of American history lies a remarkable story of independence that many outside the Lone Star State might not fully appreciate. For nearly nine years (1836-1845), Texas existed as a completely sovereign nation with its own president, constitution, currency, and diplomatic relations. This period of independence shapes Texas identity to this day and explains many of the state's unique characteristics and fierce pride.

The Republic of Texas stands as one of the few successful breakaway republics in North American history, and its journey from Mexican province to independent nation to American state reveals much about 19th-century politics, expansion, and the complex forces shaping the continent.

The Texas Revolution and Declaration of Independence

Texas independence began with increasing tensions between American settlers (called Texians) and the Mexican government. After Mexico won independence from Spain in 1821, it encouraged American settlement in Texas, but cultural and political differences soon created conflict.

The breaking point came when Mexican President Antonio López de Santa Anna abolished the 1824 constitution and centralized power. In response, Texians and Tejanos (Mexicans living in Texas) took up arms in October 1835, beginning the Texas Revolution.

On March 2, 1836, delegates gathered at Washington-on-the-Brazos and declared Texas independent from Mexico. The declaration came during the siege of the Alamo, which would fall just four days later. Despite early defeats, the Texian army under Sam Houston secured independence with a decisive victory at the Battle of San Jacinto on April 21, 1836, capturing Santa Anna himself.

Government Structure of the Republic

The Republic of Texas established a government modeled largely on the United States. Its 1836 Constitution created three branches of government and guaranteed basic rights. The republic elected Sam Houston as its first president, with subsequent administrations led by Mirabeau B. Lamar and Anson Jones.

The Republic's government structure included:

- A president serving a three-year term (not immediately eligible for re-election)

- A vice president

- A cabinet with positions including Secretary of State and Secretary of War

- A bicameral legislature with a House of Representatives and Senate

- A Supreme Court and system of lower courts

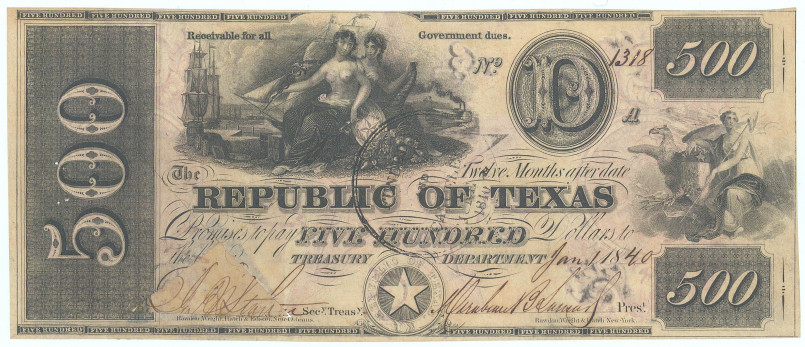

The Republic issued its own currency called the Texas dollar, though these notes often traded at severe discounts due to the republic's financial instability. The capital moved several times, from Washington-on-the-Brazos to Harrisburg, Galveston, Velasco, Columbia, Houston, and finally Austin in 1839.

Challenges Facing the Young Republic

The Republic of Texas faced enormous challenges throughout its brief existence. Chief among these was financial insecurity. The government struggled with debt, limited tax revenue, and the inability to secure substantial loans from foreign powers.

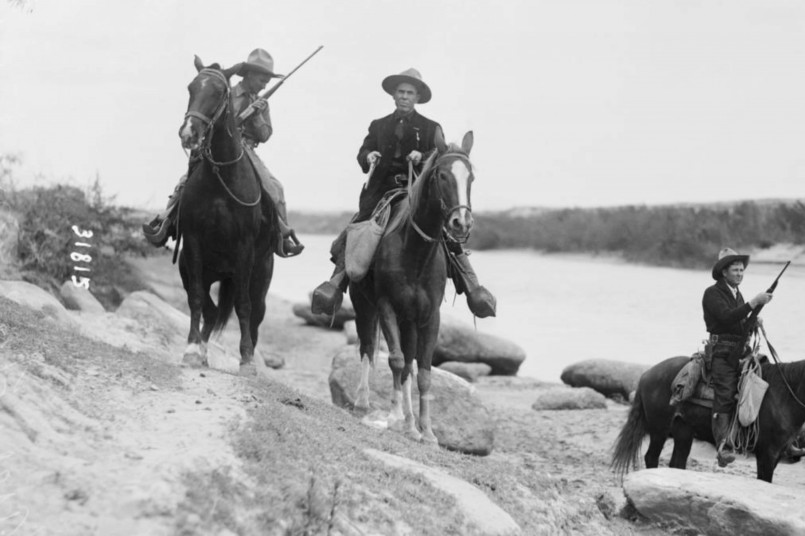

Military threats loomed large as Mexico refused to recognize Texas independence, conducting occasional raids and twice briefly occupying San Antonio. The republic maintained a small standing army and navy to defend against these incursions.

The young nation also contended with Native American conflicts, particularly with Comanche and other tribes who resisted expansion into their territories. President Lamar pursued an aggressive policy against Native Americans, while Houston favored negotiation.

Additionally, the republic faced:

- Undefined borders, with claims extending to the Rio Grande

- Limited infrastructure and transportation networks

- A small population (approximately 50,000 settlers in 1836)

- Dependence on cotton exports and imports of manufactured goods

International Relations and Diplomacy

Though its existence was brief, the Republic of Texas conducted active international diplomacy. The United States recognized Texas independence in March 1837, followed by France, Belgium, the Netherlands, and Great Britain between 1839-1841. Notably, Mexico never officially acknowledged Texas independence.

The republic established legations (diplomatic missions) in Washington, London, and Paris, and negotiated treaties covering commerce, boundaries, and extradition. Texas even attempted to secure loans and alliances with European powers, partly as leverage for eventual U.S. annexation.

President Houston initially pursued annexation by the United States, but when this stalled, his successor Lamar pivoted toward establishing Texas as a permanent independent nation. This strategy included seeking closer ties with Britain and France as counterweights to both Mexico and the U.S.

The republic also maintained a small navy that enforced a blockade against Mexico and protected Gulf shipping lanes. These ships gave Texas limited projection of power beyond its borders.

The Path to US Annexation

The question of Texas joining the United States was complicated by several factors, most prominently the issue of slavery. Texas was a slaveholding republic, and its annexation would upset the delicate balance between free and slave states in the U.S. Congress.

Initial annexation efforts under President Jackson and Van Buren failed due to these concerns. By the early 1840s, however, the political climate had changed. President John Tyler supported annexation, seeing it as beneficial to American security and expansion.

Several key developments pushed Texas toward annexation:

- Growing financial difficulties and mounting republic debt

- British diplomatic efforts that raised American fears of foreign influence

- The election of James K. Polk in 1844, who campaigned on annexation

- The concept of Manifest Destiny gaining popularity in American politics

On December 29, 1845, Texas was formally admitted to the Union as the 28th state. The republic's president, Anson Jones, transferred power to the new state government in February 1846, declaring that "the final act in this great drama is now performed; the Republic of Texas is no more."

The Legacy of the Republic of Texas

The republic era left an indelible mark on Texas identity and continues to influence the state's culture and politics. Texas retained certain unique rights upon joining the union, including:

- Keeping its public lands rather than ceding them to the federal government

- The right to divide into up to five separate states (never exercised)

- Maintaining control of offshore territories to 10.35 miles (versus 3 miles for other states)

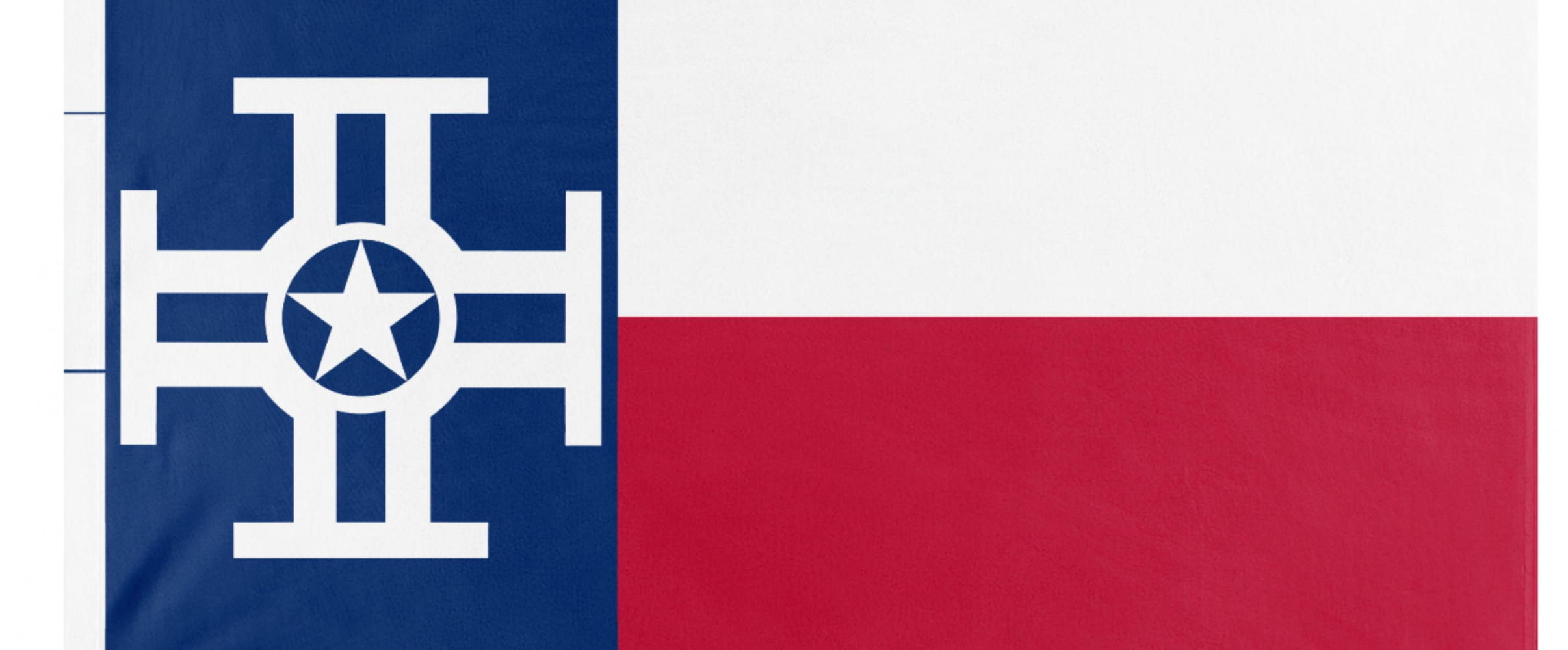

The republic's brief existence cemented a distinctive Texas nationalism that persists today. Symbols like the Lone Star flag (adopted by the republic and continued as the state flag) and the state seal date from this period and reinforce Texas' unique history.

Texas' experience as an independent nation also shaped its political culture, contributing to its strong emphasis on limited government, self-reliance, and independence. The republic era established traditions and myths that continue to influence how Texans view themselves and their relationship with the federal government.

Perhaps most significantly, the Republic of Texas represented the first major expansion of American culture and institutions beyond the original boundaries of the United States, setting the stage for the westward expansion that would define much of 19th-century American history.

Frequently Asked Questions About The Republic of Texas: When the Lone Star State Ruled Itself for 9 Years

How long was Texas its own country?

Texas existed as an independent republic for nine years, from March 2, 1836, when it declared independence from Mexico, until December 29, 1845, when it was formally admitted to the Union as the 28th U.S. state.

Why did Texas declare independence from Mexico?

Texas declared independence because of growing tensions between American settlers (Texians) and the Mexican government. Key issues included Mexico's abolition of the 1824 constitution, restrictions on immigration, attempts to enforce centralized rule, cultural differences, and disagreements over slavery, which Mexico had abolished.

Did other countries recognize the Republic of Texas?

Yes, several major powers recognized the Republic of Texas. The United States recognized Texas in March 1837, followed by France (1839), Belgium, the Netherlands, and Great Britain (1840-1841). Mexico, however, never officially recognized Texas independence.

Who was the first president of the Republic of Texas?

Sam Houston served as the first president of the Republic of Texas from October 1836 to December 1838. He was later elected to a second term (1841-1844). Houston had previously commanded the Texian Army that won independence at the Battle of San Jacinto.

Why did Texas join the United States instead of remaining independent?

Texas joined the U.S. primarily due to financial difficulties, continued military threats from Mexico, need for economic stability, and limited international support. The republic had accumulated significant debt and found independence financially unsustainable. Additionally, many Texians had American origins and cultural ties, making annexation a natural choice.

Did Texas have its own currency and military?

Yes, the Republic of Texas issued its own currency called the Texas dollar, though these notes often traded at severe discounts due to financial instability. Texas also maintained both an army and a small navy to defend against Mexican incursions and protect shipping lanes in the Gulf of Mexico.