From 1892 to 1954, Ellis Island served as the gateway to America for over 12 million immigrants seeking new opportunities. This small island in New York Harbor transformed from a military post into the nation's busiest immigration inspection station, forever changing American society and culture.

In the shadow of the Statue of Liberty, a small island in New York Harbor became the symbol of American immigration and hope for millions. Ellis Island, once an obscure piece of land used for hanging pirates, would transform into the nation's busiest immigration processing center, where over 12 million immigrants took their first steps toward American citizenship between 1892 and 1954.

This transformation didn't happen overnight. Ellis Island's evolution from military post to immigration gateway reflected America's changing relationship with immigration, shaped by economic needs, cultural anxieties, and humanitarian ideals that continue to influence immigration policy today.

Ellis Island Before Immigration

Before becoming synonymous with immigration, Ellis Island had a varied history. Originally called "Gull Island" by the Mohegan Indians, the island was barely three acres of sand and mud that would disappear at high tide. Dutch settlers later named it "Oyster Island" for the abundant shellfish beds surrounding it.

The island was purchased by Samuel Ellis in the 1770s, giving it the name we know today. After Ellis's death, the island became federal property in 1808. The U.S. government used it primarily as a military post and powder magazine for nearly a century.

By the late 19th century, immigration had been handled by individual states rather than the federal government. In New York, Castle Garden Immigration Depot in Manhattan served as the main immigration station from 1855 to 1890. However, as immigration numbers grew, so did corruption and inefficiency at Castle Garden.

Opening America's Golden Door

The federal government took control of immigration processing in 1890, and Congress appropriated $75,000 to build a proper immigration station on Ellis Island. The island was expanded through landfill to about six acres, and an impressive Georgian-style building was constructed.

On January 1, 1892, Ellis Island officially opened with much fanfare. The first immigrant processed was Annie Moore, a 15-year-old girl from County Cork, Ireland, traveling with her two younger brothers to join their parents who had already settled in New York.

Just five years later, disaster struck when a fire destroyed the wooden immigration buildings on June 15, 1897. Fortunately, no lives were lost, but most of the immigration records dating back to 1855 were destroyed. The facility was rebuilt with fireproof materials, and a much larger, more imposing red brick building opened in December 1900.

Processing Immigrants

For most immigrants, the processing experience at Ellis Island was brief but intense. First and second-class passengers were typically inspected aboard ship and allowed to enter the country immediately. It was primarily steerage or third-class passengers who underwent the full Ellis Island inspection process.

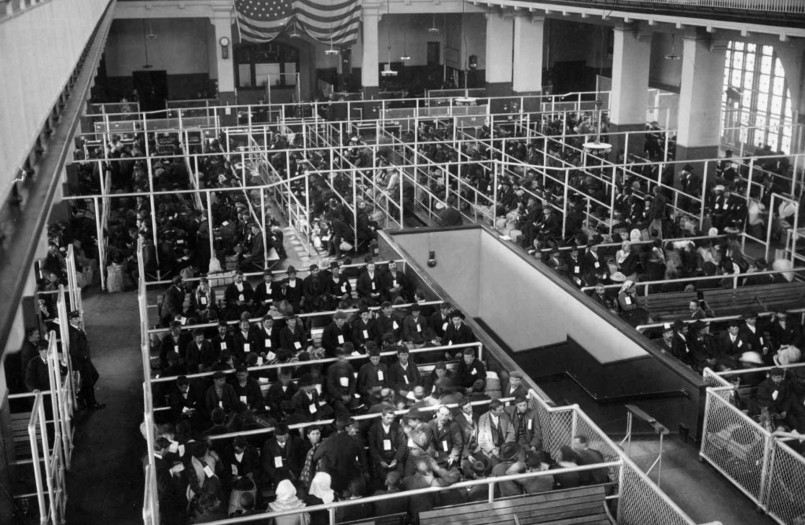

Upon arrival, immigrants climbed the stairs to the Great Hall, often called the "Stairs of Separation" because it was the first step in a process that would determine their fate. In the Great Hall, they waited in long lines to be processed, sometimes for hours.

Inspectors asked immigrants 29 questions, including name, occupation, and destination. Many immigrants had their names changed or simplified during this process-not because officials deliberately changed them, but due to miscommunications, language barriers, or immigrants' own desire to Americanize their names.

The Registry Room Experience

The cavernous Registry Room (Great Hall) processed up to 5,000 people per day during peak immigration years. The room's high-vaulted ceiling was designed to intimidate, while also helping officials observe immigrants from elevated walkways, looking for signs of illness or distress.

For most immigrants, the entire process took between three and five hours. Those who passed inspection received landing cards that permitted them to leave Ellis Island and enter the United States.

Medical Inspections

Medical examinations were perhaps the most feared part of the process. As immigrants climbed the stairs to the Registry Room, medical officers would watch for signs of respiratory distress or lameness. They examined eyes for trachoma, a contagious eye disease, using buttonhooks to flip the eyelid.

Doctors at Ellis Island became experts at rapid diagnosis. They could identify numerous physical conditions that might make an immigrant "likely to become a public charge" (LPC), a designation that could result in deportation.

Those suspected of having medical issues were marked with chalk on their clothing-L for lameness, H for heart problems, X for mental illness. These individuals would be detained for further examination, sometimes for weeks.

Detainment and Deportation

About 20 percent of arrivals at Ellis Island were detained for medical treatment or further questioning. The island had hospital facilities that could accommodate up to 275 patients. Those with curable conditions might be treated and later released.

Immigrants could also be detained for legal reasons. Those suspected of being contract laborers (workers who had agreed to jobs before immigrating, which was illegal under the 1885 Contract Labor Law) or those with criminal backgrounds might be held for special inquiry boards.

While most immigrants were eventually cleared to enter the United States, about 2 percent were denied entry and deported. The steamship companies were responsible for returning these individuals to their countries of origin, a policy that encouraged the companies to screen passengers before departure.

Immigration Acts and Decline

The peak years of immigration through Ellis Island were from 1905 to 1914, with a record 1.25 million immigrants processed in 1907 alone. During World War I, immigration numbers declined sharply, and the facility was used primarily as a detention center for enemy aliens.

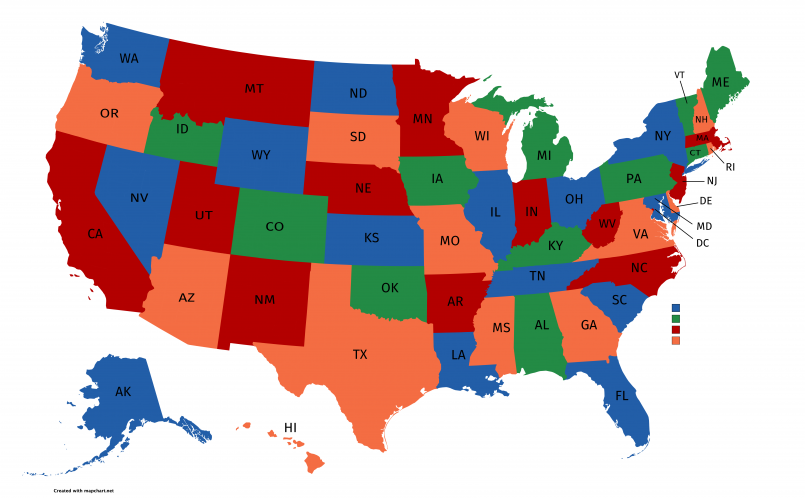

The Immigration Act of 1924 significantly restricted immigration by establishing national origins quotas that favored Northern and Western Europeans. This legislation also specified that immigrants should be inspected in U.S. consulates abroad before departing for America, reducing Ellis Island to processing only unusual or problematic cases.

By the 1930s, Ellis Island was primarily used for detaining and deporting immigrants who had entered illegally or violated the terms of their admission. During World War II, the island again served as a detention center for enemy aliens, primarily Germans, Italians, and Japanese.

Ellis Island Today

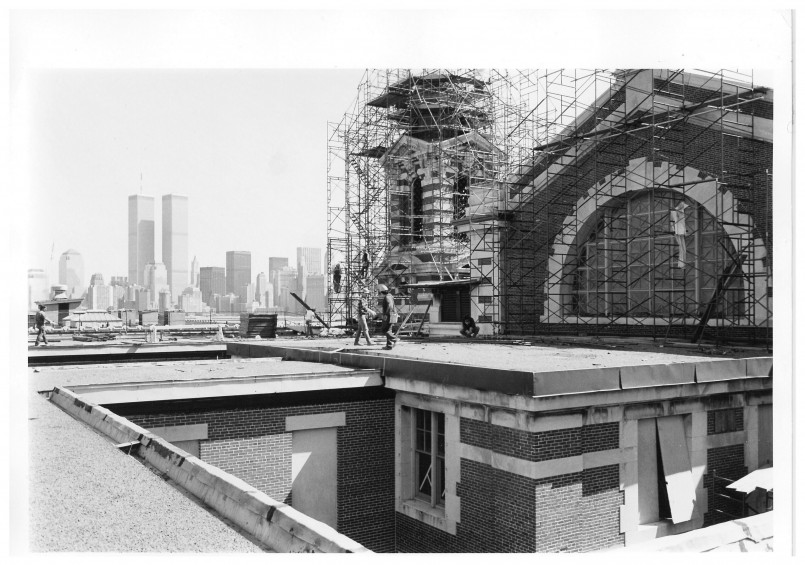

Ellis Island officially closed as an immigration station on November 12, 1954. For decades afterward, the buildings fell into disrepair until 1965, when President Lyndon B. Johnson incorporated the island into the Statue of Liberty National Monument.

After extensive restoration, the Ellis Island Immigration Museum opened to the public in 1990. Today, the museum receives nearly 2 million visitors annually, many of whom are descendants of immigrants who passed through its halls.

The American Family Immigration History Center at Ellis Island allows visitors to search ship passenger manifests containing information about their ancestors who came through the port of New York between 1892 and 1957.

Ellis Island remains a powerful symbol of America's immigrant heritage. More than 40 percent of Americans can trace at least one ancestor who passed through Ellis Island, making it a profound connection to personal and national identity for millions of Americans.

Frequently Asked Questions About The Fascinating Story of Ellis Island: America's Historic Immigration Gateway

Why was Ellis Island chosen as an immigration station?

Ellis Island was chosen primarily for its isolated location in New York Harbor, which made it ideal for quarantine purposes. It was also federal property, easily accessible from the main shipping lanes, and could be expanded through landfill to accommodate growing numbers of immigrants. Its proximity to Manhattan but physical separation from it allowed for controlled processing of immigrants before they entered the mainland.

Did officials at Ellis Island change immigrants' names?

Contrary to popular belief, officials did not deliberately change immigrants' names. Name changes typically occurred due to several factors: immigrants themselves choosing to Americanize their names, miscommunications due to language barriers, or clerical errors. Inspectors used ship manifests prepared at the ports of departure, so any name recorded at Ellis Island would have matched the name on the ship manifest.

What happened to immigrants who were denied entry?

Approximately 2% of immigrants were denied entry and deported. Reasons included contagious diseases, criminal backgrounds, suspicion of becoming public charges, or violating immigration laws. Steamship companies were responsible for returning these individuals to their countries of origin at the companies' expense, which encouraged them to screen passengers carefully before departure.

What is the "kissing post"?

The "kissing post" was the nickname given to the area where immigrants who had passed inspection at Ellis Island reunited with family members who had come to meet them. Located at the exit of the Registry Room, it was the scene of emotional reunions as family members embraced after long separations, hence the name.

When is the best time to visit Ellis Island today?

The best time to visit Ellis Island is during weekday mornings in the spring or fall when crowds are smaller. Summer months and weekends can be extremely crowded, with long waits for the ferry. Winter visits offer the fewest crowds but ferry schedules may be limited due to weather conditions. Purchasing tickets in advance online is highly recommended regardless of when you visit.