Washington D.C. occupies a unique position in American governance - a federal district created specifically to house the seat of government, yet not granted statehood. This article explores the constitutional foundations, historical reasons, and ongoing debates surrounding D.C.'s special status.

In the American system of government, Washington D.C. stands as a constitutional anomaly - a capital city that isn't part of any state. While residents pay federal taxes and serve in the military, they lack the full congressional representation enjoyed by citizens living in the 50 states. This unique status was intentional in the nation's founding but has become increasingly controversial in modern times.

The District of Columbia spans just 68 square miles, making it smaller than every state, yet its population exceeds that of several states. Despite this, D.C. remains in political limbo, neither a territory nor a state, but a federal district with its own particular governance structure and limitations.

Constitutional Foundations

The primary reason Washington D.C. isn't a state lies in the Constitution itself. Article I, Section 8, Clause 17 (known as the District Clause) explicitly grants Congress the power "to exercise exclusive Legislation in all Cases whatsoever, over such District (not exceeding ten Miles square) as may, by Cession of particular States, and the Acceptance of Congress, become the Seat of Government of the United States."

The Founding Fathers deliberately created this federal district to house the national capital outside the jurisdiction of any individual state. James Madison argued in Federalist No. 43 that the federal government needed to have authority over its own seat of government to maintain independence and prevent undue influence from any state.

Historical Context

The decision to create a federal district stemmed from a pivotal incident in 1783 when the Continental Congress was meeting in Philadelphia. Angry soldiers surrounded Independence Hall demanding back pay, and Pennsylvania state authorities refused to provide protection. This demonstrated to the founders the danger of relying on a state government for the capital's security.

The Residence Act of 1790 established the new federal district, with land donated by Maryland and Virginia along the Potomac River. President Washington himself selected the exact site. Originally, the District was a perfect 10-mile square, though the portion from Virginia was later returned (now Alexandria and Arlington County).

Federal Authority Concerns

A fundamental reason D.C. remains a district rather than a state is the concern that statehood would create conflicts between federal and state authority. The federal government might face limitations if the capital were subject to a state government's jurisdiction.

Imagine a scenario where a state government could potentially interfere with federal operations, influence national policy through local regulations, or even impede congressional proceedings. These concerns, while perhaps less pressing in modern governance, remain central to constitutional arguments against D.C. statehood.

Size and Population

Washington D.C.'s physical size and population have both been cited in arguments against statehood. At just 68 square miles, D.C. would be significantly smaller than Rhode Island, the current smallest state. However, population-wise, D.C.'s approximately 700,000 residents exceeds that of Vermont and Wyoming.

The district's economy is heavily dependent on the federal government, with federal employees and related industries comprising a substantial portion of its workforce. Critics argue this creates a potential conflict of interest, as the jurisdiction housing the federal government would have disproportionate interest in expanding it.

Representation Without Statehood

D.C. residents' status has evolved over time. Until 1961, residents couldn't even vote in presidential elections. The 23rd Amendment granted D.C. presidential electoral votes (equal to the least populous state, but no more than three). In 1970, D.C. gained a non-voting delegate to the House of Representatives.

The district's local governance has also transformed. In 1973, Congress passed the Home Rule Act, allowing D.C. to elect its own mayor and city council. However, Congress maintains ultimate authority, with the power to review and overturn local laws and control the district's budget.

The Statehood Movement

The movement for D.C. statehood has gained significant momentum in recent decades. Advocates argue that the district's taxation without representation (a phrase that appears on D.C. license plates) violates the democratic principles upon which the nation was founded.

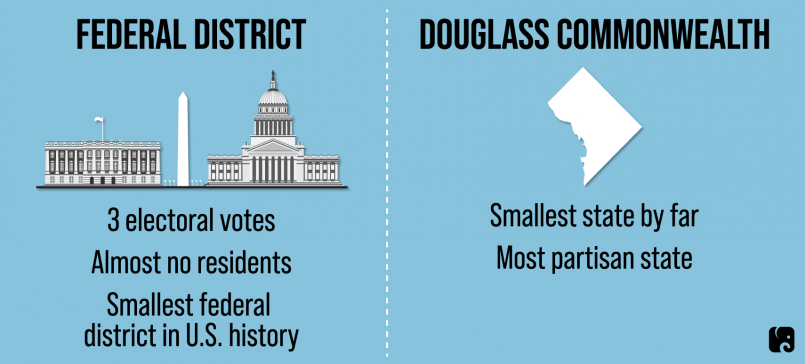

Statehood proposals typically suggest creating a smaller federal district containing only the key government buildings (White House, Capitol, Supreme Court, etc.), while converting the residential and commercial areas into a new state. The proposed name is often the State of Washington, Douglass Commonwealth (honoring both George Washington and Frederick Douglass).

Proposed Alternatives

Various alternatives to statehood have been proposed over the years. These include:

- Retrocession to Maryland (similar to how Virginia's portion was returned)

- A constitutional amendment granting D.C. voting representation in Congress while remaining a district

- Limited home rule expansion with greater autonomy but no full statehood

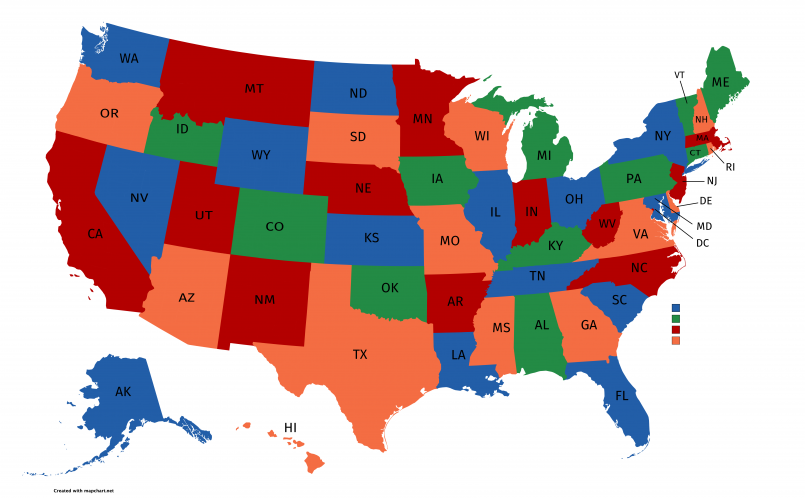

Each proposal carries its own constitutional complexities and political challenges. The debate often splits along partisan lines, with Democrats generally supporting statehood and Republicans opposing it - a division partly influenced by D.C.'s heavily Democratic-leaning electorate.

The question of Washington D.C.'s status remains unresolved, balancing constitutional design against democratic representation. As the nation continues to evolve, this fundamental question about the capital's governance will likely remain at the forefront of American political discourse.

Frequently Asked Questions About The Unique Status of Washington D.C.: 7 Reasons It's Not a State

Could Washington D.C. ever become a state?

Yes, it's constitutionally possible. The most likely path would involve creating a smaller federal district containing only government buildings while converting the residential areas into a new state. This would require passing legislation in both houses of Congress and presidential approval. However, there are significant political hurdles, as the issue has become partisan with Democrats generally supporting and Republicans opposing statehood.

Do Washington D.C. residents pay federal taxes?

Yes, D.C. residents pay all federal taxes, including income tax, despite not having voting representation in Congress. This situation has led to the adoption of the phrase "taxation without representation" on D.C. license plates, echoing a key grievance from the American Revolution.

How does Washington D.C. govern itself if it's not a state?

Since the Home Rule Act of 1973, D.C. has had an elected mayor and 13-member city council that handle local governance. However, Congress maintains ultimate authority over the district, with the power to review and overturn local laws and control D.C.'s budget. This arrangement gives D.C. residents less autonomy than citizens of the 50 states.

What was the original size of Washington D.C.?

Originally, Washington D.C. was a perfect 10-mile square (100 square miles) with territory donated by both Maryland and Virginia. In 1846, the Virginia portion (about 31 square miles) was returned to that state and is now Alexandria and Arlington County. The current D.C. is only the land that was ceded by Maryland.

What are the political implications of D.C. statehood?

D.C. statehood would likely result in two additional Democratic senators and one voting Democratic representative, as the district consistently votes overwhelmingly Democratic. This political reality is one reason the issue has become partisan, with Republicans generally opposing statehood as it would likely shift the balance of power in Congress.