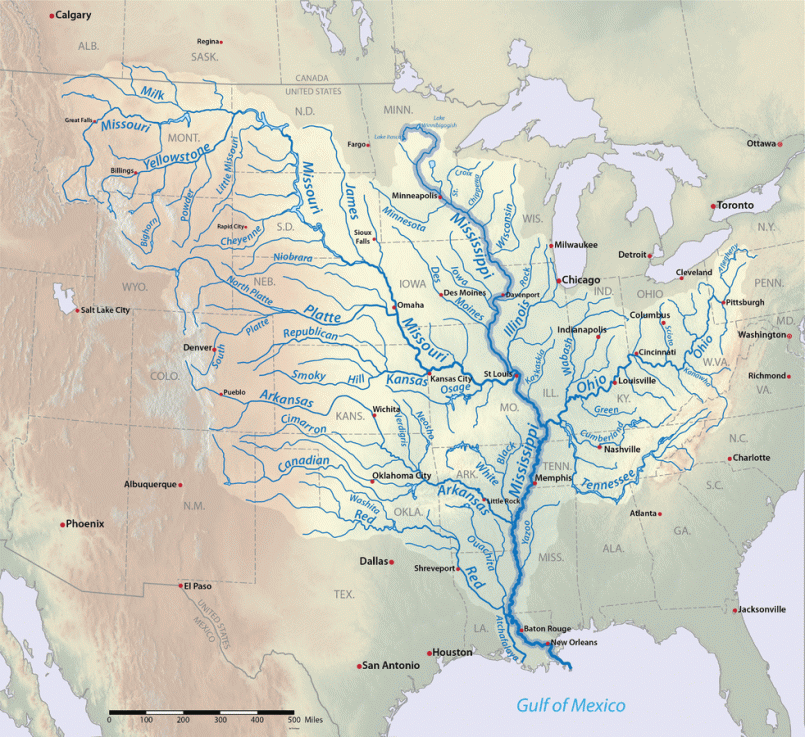

The Mississippi River Basin forms the largest navigable waterway system on Earth, spanning 1.2 million square miles across 31 U.S. states and parts of Canada. This massive network includes over 12,000 miles of navigable channels, serves as a vital transportation artery for America's heartland, and supports 30% of U.S. waterborne commerce.

The Mississippi River Basin stands as one of humanity's most remarkable natural assets and engineering achievements. Spanning 1.2 million square miles across the heart of North America, this vast watershed encompasses the Mississippi River and its hundreds of tributaries, creating the largest navigable waterway system on Earth . From the northern reaches of Minnesota to the Gulf of Mexico, this intricate network of rivers has shaped American history, culture, and commerce for centuries.

What makes the Mississippi Basin truly extraordinary is not just its size, but its navigability . With over 12,000 miles of commercially navigable waterways connecting 31 states and two Canadian provinces, the system functions as America's internal maritime highway, moving vast quantities of goods through the nation's heartland with remarkable efficiency.

Geography and Scale: America's Inland Maritime Highway

The Mississippi River Basin drains about 41% of the continental United States , creating a vast hydrological system that includes major rivers like the Missouri, Ohio, Arkansas, and Tennessee. The main stem Mississippi River alone stretches approximately 2,340 miles from its source at Lake Itasca in Minnesota to its delta in Louisiana, making it the second-longest river in North America after the Missouri-Mississippi system combined.

What truly distinguishes this basin is its exceptional navigability. Unlike many of the world's great rivers that feature impassable rapids or waterfalls, the Mississippi system offers continuous navigation throughout much of its length. The main channel provides a minimum 9-foot deep navigation channel for over 1,800 miles upstream from New Orleans, allowing oceangoing vessels to reach as far north as Minneapolis.

The basin's geography encompasses incredible diversity, from the northern hardwood forests to the agricultural heartland of the Midwest, through the lower Mississippi's vast alluvial plain. This geographic variety has made the river system crucial for transporting different regional products - grain from the Midwest, coal from Appalachia, and manufactured goods from urban centers.

Historical Significance: Shaping a Nation

Long before European settlement, Native American tribes recognized the Mississippi as a vital transportation corridor . The river's name itself comes from the Anishinaabe (Ojibwe) word "Misi-ziibi," meaning "Great River." Following European exploration, the river quickly became central to America's westward expansion.

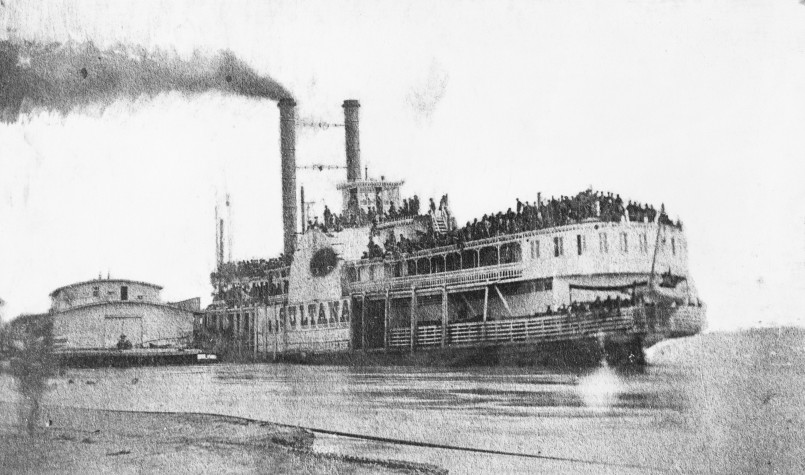

The 1803 Louisiana Purchase , which doubled the size of the United States, was largely motivated by President Jefferson's desire to secure American navigation rights on the Mississippi. The river subsequently became the backbone of 19th-century commerce, with steamboats transforming the American interior from frontier territory to economic powerhouse.

Mark Twain, who worked as a riverboat pilot before becoming America's celebrated author, captured the river's significance in his writings: "The Mississippi River will always have its own way; no engineering skill can persuade it to do otherwise." The river's cultural importance remains embedded in American literature, music, and identity.

Economic Importance: America's Commercial Lifeline

Today, the Mississippi River system functions as America's most important commercial waterway. The basin carries an astonishing 60% of all U.S. grain exports , including corn and soybeans bound for international markets. Overall, the system transports more than 500 million tons of cargo annually , valued at over $130 billion.

This maritime highway serves as a cost-effective alternative to rail and truck transport. A single 15-barge tow can carry the equivalent of 216 rail cars or 1,050 large semi-trucks. The fuel efficiency is equally impressive, with barges able to move one ton of cargo 647 miles on a single gallon of fuel, compared to 477 miles by rail and 145 miles by truck.

Key Economic Statistics

The Mississippi Basin waterway system:

- Supports over 1.3 million jobs nationwide

- Generates more than $580 billion in economic activity annually

- Handles approximately 30% of all U.S. waterborne commerce

- Serves 92% of America's agricultural exports

- Connects major industrial centers in Minneapolis, St. Louis, Memphis, and New Orleans

Environmental Challenges and Conservation Efforts

The Mississippi Basin faces significant environmental challenges despite its economic importance. Centuries of modifications for navigation and flood control have dramatically altered the river's natural hydrology. The channelization of the river through levees, wing dikes, and revetments has disconnected the river from its floodplain and accelerated the loss of coastal wetlands in Louisiana.

Agricultural runoff from the basin creates another major environmental concern. Fertilizer and soil washing into the river system has created a massive "dead zone" in the Gulf of Mexico, an oxygen-depleted area that can reach the size of New Jersey. This hypoxic zone severely impacts marine life and commercial fisheries.

In response to these challenges, numerous conservation initiatives have emerged. The Mississippi River Basin Healthy Watersheds Initiative works with farmers to implement conservation practices that reduce nutrient runoff. Organizations like The Nature Conservancy and American Rivers are working to restore floodplains and wetlands that provide natural flood protection and wildlife habitat.

Navigation Infrastructure: Locks, Dams and Channels

The Mississippi Basin's navigability didn't happen by accident. It represents one of humanity's most extensive engineering achievements. The system includes 29 lock and dam complexes on the Upper Mississippi alone, creating a "stairway of water" that allows vessels to navigate the river's natural elevation changes.

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers maintains this massive infrastructure, continuously dredging channels to maintain minimum depths and operating the locks that raise and lower vessels between pool levels. The typical lock on the Upper Mississippi measures 600 feet long by 110 feet wide, accommodating a tow of up to 15 barges arranged three wide by five long.

Further south, the Lower Mississippi doesn't require locks and dams but demands constant channel maintenance . The Corps dredges approximately 100 million cubic yards of sediment annually to maintain the navigation channel, a volume that would fill the Superdome in New Orleans more than 14 times.

Major Infrastructure Components

The navigation system includes:

- 29 locks and dams on the Upper Mississippi River

- 43 locks and dams on the Ohio River system

- Eight locks and dams on the Missouri River

- Thousands of river training structures (wing dikes and revetments)

- The Old River Control Structure in Louisiana, which prevents the Mississippi from changing course into the Atchafalaya River

Tourism and Recreation Along the Mississippi

Beyond commerce, the Mississippi Basin offers tremendous recreational opportunities. River cruises have experienced a renaissance, with companies like American Cruise Lines and Viking offering multi-day journeys that trace the paths of historic steamboats. Cities along the river have revitalized their waterfronts, creating parks, trails, and entertainment districts that celebrate their riverine heritage.

The Great River Road , a scenic byway following the Mississippi's course through ten states, attracts tourists to historic river towns, cultural sites, and natural areas. Recreational boating, fishing, hunting, and wildlife watching generate billions in additional economic activity throughout the basin.

For outdoor enthusiasts, the Upper Mississippi River National Wildlife and Fish Refuge protects 240,000 acres along 261 miles of river. This corridor serves as critical habitat on the Mississippi Flyway, a migration route used by nearly 40% of North America's waterfowl and 60% of all bird species.

The Future of the Mississippi River Basin

The Mississippi Basin faces significant challenges in the coming decades. Much of the navigation infrastructure, built in the 1930s, is reaching the end of its designed lifespan. The American Society of Civil Engineers has assigned a "D" grade to America's inland waterway infrastructure, highlighting the need for massive reinvestment.

Climate change presents another challenge, with increasing frequency of both flooding and drought conditions affecting navigation. The historic flood of 2019 halted river traffic for months, while drought in 2012 nearly closed the river to navigation due to low water levels.

Despite these challenges, the basin's future appears bright. Recent federal infrastructure investments, including the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act of 2021 , allocated billions for inland waterway improvements. New technologies are making river transportation more efficient and environmentally friendly, including hybrid-powered towboats and automated navigation systems.

As America confronts the challenges of climate change and economic competition, the Mississippi Basin's unmatched capacity for low-carbon, efficient transportation positions it to remain the nation's most important inland waterway for generations to come.

Frequently Asked Questions About Mississippi River Basin is Earth's Largest Navigable Waterway System

Why is the Mississippi River Basin considered the largest navigable system on Earth?

The Mississippi River Basin is considered the largest navigable system on Earth because it contains over 12,000 miles of commercially navigable waterways connecting 31 U.S. states and parts of Canada. Unlike other major river systems that have impassable sections, the Mississippi system offers continuous navigation throughout much of its length, with a maintained minimum 9-foot channel depth for over 1,800 miles from the Gulf of Mexico to Minneapolis, allowing for year-round commercial shipping.

How does shipping on the Mississippi River compare to rail and truck transportation?

Mississippi River shipping is significantly more efficient than rail or truck transportation. A single 15-barge tow can carry the equivalent of 216 rail cars or 1,050 large semi-trucks. The fuel efficiency is remarkable, with barges moving one ton of cargo 647 miles on a single gallon of fuel, compared to 477 miles by rail and just 145 miles by truck. This efficiency makes river transport both more economical and more environmentally friendly for bulk commodities.

What types of cargo are primarily transported on the Mississippi River system?

The Mississippi River system primarily transports bulk commodities including agricultural products (60% of all U.S. grain exports move down the river), petroleum products, coal, chemicals, cement, and steel. The system is especially important for agricultural exports, handling approximately 92% of America's agricultural exports. Manufactured goods, construction materials, and industrial components are also significant cargo categories.

How do seasonal changes affect navigation on the Mississippi River?

Seasonal changes significantly impact Mississippi River navigation. Spring flooding can increase current speeds, making upstream navigation more difficult and sometimes forcing temporary closures when water levels exceed lock heights. Winter brings ice formation on the Upper Mississippi, typically closing that section from December through March. Summer and fall drought conditions can create low water that reduces barge capacity or stops navigation entirely, as happened during severe droughts in 2012 and 2022.

What environmental challenges does the Mississippi River Basin face?

The Mississippi Basin faces several major environmental challenges including agricultural runoff that creates the Gulf of Mexico "dead zone," loss of wetlands and floodplain connectivity due to levees and channelization, invasive species like Asian carp, increased flooding frequency due to climate change, and legacy industrial pollution. Conservation efforts focus on reducing nutrient runoff, restoring floodplains, improving sediment management, and upgrading aging infrastructure to better balance navigation needs with ecosystem health.

How can tourists experience the Mississippi River Basin?

Tourists can experience the Mississippi River Basin through multiple options including multi-day river cruises on replicated steamboats or modern vessels, driving the Great River Road scenic byway that follows the river through ten states, visiting riverfront attractions in cities like St. Louis, Memphis and New Orleans, exploring state parks and wildlife refuges along the shorelines, renting houseboats, taking day-trip excursions, visiting historic sites related to river commerce, or cycling portions of the Mississippi River Trail that follows the river from Minnesota to Louisiana.