The Lewis and Clark Expedition (1804-1806) was a pivotal moment in American history when Meriwether Lewis and William Clark led the Corps of Discovery westward, charting unknown territories from the Mississippi to the Pacific Ocean. Their journey revealed the true breadth of the continent, documented hundreds of new species, and established the first official American contact with numerous Native American tribes.

In May 1804, Meriwether Lewis and William Clark embarked on one of the most ambitious explorations in American history. Commissioned by President Thomas Jefferson following the Louisiana Purchase, their expedition would traverse nearly 8,000 miles of largely unmapped territory, forever changing America's understanding of its western frontier.

The Corps of Discovery battled harsh weather, dangerous rapids, grizzly bears, and illness while meticulously documenting hundreds of plant and animal species previously unknown to science. Their journals, maps, and specimens would provide the first scientific record of the American West and establish the foundation for westward expansion.

Expedition Origins: Jefferson's Vision

President Thomas Jefferson orchestrated the expedition in the wake of the Louisiana Purchase of 1803, which doubled the size of the United States overnight. Jefferson, a scientist and visionary, sought to understand the vast territories America had acquired and to establish an American presence in lands contested by European powers.

Jefferson provided Lewis with specific instructions: find a navigable water route to the Pacific Ocean, document the flora and fauna, establish trade with Native American tribes, and assert American sovereignty over the region. The expedition was as much a scientific mission as it was a geopolitical one.

The Corps of Discovery

Lewis and Clark carefully selected approximately 45 men to form their "Corps of Discovery." These included soldiers, hunters, interpreters, and boatmen with specific skills needed for the journey. Among them was York, Clark's enslaved man, who would become the first African American to cross the continent and whose contributions were vital to the expedition's success.

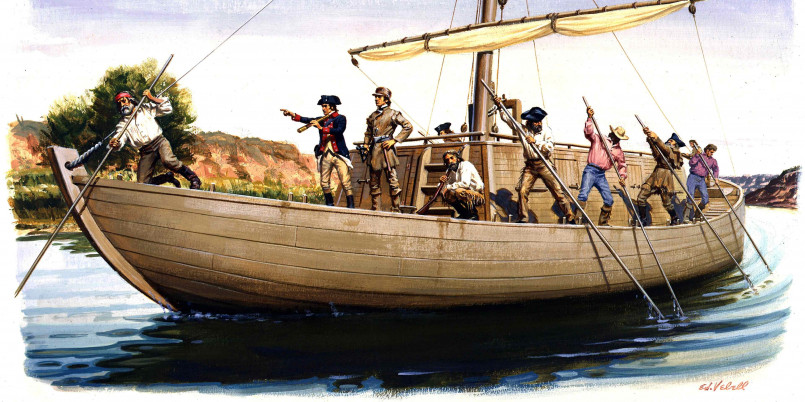

The corps traveled in a 55-foot keelboat and two pirogues (dugout canoes) up the Missouri River. Their supplies included weapons, scientific instruments, medicine, trade goods for Native Americans, and enough food to sustain them during the winter months.

Sacagawea: Essential Guide

In the winter of 1804-1805, the expedition established Fort Mandan in present-day North Dakota. There they met Sacagawea, a young Shoshone woman who was pregnant and living with her French-Canadian husband Toussaint Charbonneau, who was hired as an interpreter.

Sacagawea joined the expedition with her infant son Jean Baptiste, born in February 1805. Her knowledge of the land, ability to find edible plants, and skills as a translator proved invaluable. Perhaps most importantly, her presence signaled peaceful intentions to tribes they encountered, as war parties did not travel with women and children.

Scientific Discoveries

The expedition documented over 178 new plants and 122 animal species previously unknown to science, including the grizzly bear, pronghorn antelope, mountain beaver, and the prairie dog. Lewis meticulously collected specimens, preserved seeds, and created detailed botanical drawings.

Their journals described the geography of the West with remarkable accuracy, noting mountain ranges, river systems, and natural landmarks. These scientific observations provided the first comprehensive record of the region's natural resources and biodiversity, information that would prove crucial for future settlement.

Native American Encounters

Throughout their journey, Lewis and Clark met with approximately 50 Native American tribes. Jefferson had instructed them to establish diplomatic relations, observe customs, and assess the potential for trade. The explorers conducted ceremonies declaring American sovereignty, distributed peace medals featuring Jefferson's likeness, and collected ethnographic information about tribal languages, governance, and lifestyles.

While many encounters were peaceful-with tribes like the Mandan, Hidatsa, and Nez Perce providing crucial assistance-others were tense. The expedition narrowly avoided conflict with the Teton Sioux and had a deadly skirmish with the Blackfeet, the only violent incident of the journey.

Crossing the Continental Divide

One of the expedition's most significant challenges came in crossing the Rocky Mountains in 1805. Jefferson had hoped for an easy water passage across the continent, but Lewis and Clark discovered the formidable reality of the Continental Divide.

The crossing required abandoning their boats, acquiring horses from the Shoshone (facilitated by Sacagawea, who discovered the negotiating chief was her brother), and traversing the Bitterroot Mountains along the difficult Lolo Trail. This arduous passage nearly ended in disaster as the men faced starvation and freezing conditions before descending to the Columbia River basin.

Reaching the Pacific

On November 7, 1805, William Clark wrote in his journal: "Ocean in view! O! The joy!" The expedition had reached the mouth of the Columbia River and the Pacific Ocean. They constructed Fort Clatsop near present-day Astoria, Oregon, where they endured a rain-soaked winter before beginning their return journey in March 1806.

While at Fort Clatsop, they continued their scientific work, interacted with local Clatsop and Chinook tribes, and prepared detailed maps of their route. The confirmation that the continent could be traversed from east to west represented the fulfillment of a major expedition objective.

Expedition Legacy

When Lewis and Clark returned to St. Louis in September 1806, they were initially presumed dead. Their successful return was celebrated throughout the nation, and their discoveries fundamentally changed Americans' understanding of their continent.

The expedition's legacy includes the first accurate maps of the American West, scientific knowledge that advanced multiple fields, and diplomatic relationships with Native American nations. Their journey established American claims to the Oregon Territory and inspired a generation of trappers, traders, and eventually settlers to venture westward.

Today, the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail stretches 4,900 miles across sixteen states, preserving the routes and stories of this remarkable journey that helped shape the American identity and define a nation's ambitions.

Frequently Asked Questions About Lewis and Clark Expedition: 12 Remarkable Discoveries That Changed America

What was the main purpose of the Lewis and Clark Expedition?

The expedition had multiple objectives set by President Jefferson: to find a navigable water route to the Pacific (the "Northwest Passage"), document new plant and animal species, establish relations with Native American tribes, assert American sovereignty over the newly purchased Louisiana Territory, and conduct scientific observations throughout the journey.

How did Sacagawea help the Lewis and Clark Expedition?

Sacagawea provided crucial assistance as an interpreter with Shoshone and other tribes, helped identify edible plants and food sources, facilitated the acquisition of horses needed to cross the Rocky Mountains, and importantly, her presence with her infant son signaled peaceful intentions to tribes they encountered, as war parties would not travel with women and children.

Did Lewis and Clark actually find the Northwest Passage?

No, one of the expedition's key discoveries was that Jefferson's hope for an easy water route across the continent was impossible. They found that the Rocky Mountains required an arduous overland crossing, disproving the existence of a convenient Northwest Passage by water. This reality significantly impacted future transportation planning across the continent.

What scientific contributions came from the expedition?

The expedition documented 178 new plant species and 122 new animal species, including the grizzly bear, pronghorn antelope, and prairie dog. They created the first accurate maps of the western territories, recorded weather data, described geographical features, and gathered information about Native American cultures. These scientific records formed the foundation of American understanding of western resources.

How did Native American tribes respond to Lewis and Clark?

Responses varied greatly among the approximately 50 tribes they encountered. Many were hospitable and provided critical assistance, particularly the Mandan, Hidatsa, and Nez Perce. The Shoshone supplied horses essential for mountain crossing. Some encounters were tense, especially with the Teton Sioux. Only one violent conflict occurred, with the Blackfeet tribe during the return journey.

How did the expedition change America's understanding of its territory?

Before Lewis and Clark, much of the West was literally blank space on American maps. Their detailed journals, maps, and specimens revealed the true scale of the continent, its mountain ranges, river systems, native populations, and natural resources. This knowledge transformed how Americans perceived their country's potential, directly inspiring the westward expansion that would define the 19th century.